In 1871, Japan was still being introduced to the United States as a country with an actual civilization. “The population of Japan,” wrote a Missouri Republican journalist in September 1871, “has been variously estimated from twenty-five to forty million. Hitherto we have had no reliable statistics upon which to base an opinion.” Also, according to scholar Edward R. Beauchamp’s groundbreaking article in Monumenta Nipponica, there were fewer than an estimated 2,200 Westerners living in the Kanto area at the time. Reports back home in English were either greatly embellished or vague and underwhelming.

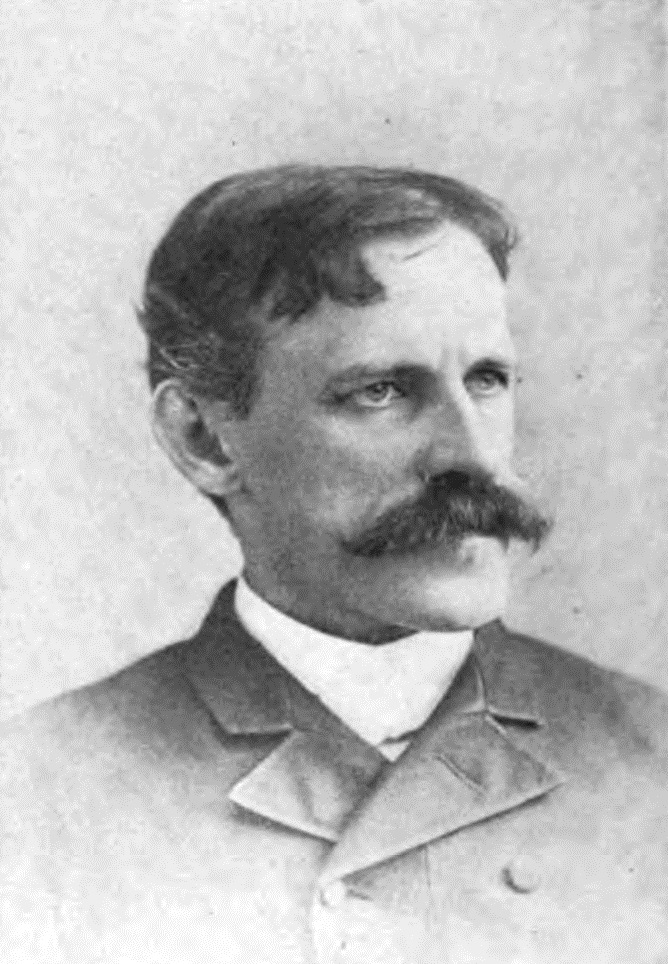

Still, the United States was ready to at least attempt to understand the intricacies of Japanese culture. Ever since Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s 1853-1854 expeditions, Japan had finally started to open its borders and trade with other countries — mainly Russia, Germany, France, Britain and the U.S. Perry’s historic trip also managed to capture the imagination of the younger generation. One young man, 9-year-old William Elliot Griffis, remembered watching the Susquehanna leave his father’s coal wharf to join Perry’s fleet.

In 1860, Griffis, then a high school graduate living in Philadelphia, managed to greet in person several Japanese officials who’d come to the U.S. to formally create the first U.S.-based Japanese embassy. Their demeanor had an impact on the young man: “From the first,” he recalled many years later, “I took the Japanese seriously. In many respects our equals, in others they seemed to be our superiors.”

Motivation

By the end of the 1860s, Griffis had survived the American Civil War (briefly Union-enlisted) and graduated from Rutgers University in 1869. His studies included classes in German, French, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, history, botany, physics, chemistry and astronomy. It was in his Latin studies where he tutored and befriended Fukui resident Taro Kusakabe, who’d been sent by Fukui officials to complete a Western education and apply what he learned to his home region. Sadly, however, Kusakabe died of tuberculosis just before graduating in 1870, affecting Griffis greatly.

Eventually, in the early fall of 1870, Griffis was invited to teach science at a new, progressively minded school in Japan. The opportunity was risky, and his family did not want him to go. But, as the aspiring minister described to his sister Margaret, the decision could be beneficial.

“I can study and be ordained there,” he wrote on September 26, 1870, “and God willing, return to my native land, only one year later than if I stayed. Besides the grand opportunities and culture, travel and good climate, and being under the special protection of the Prince, I can not only study my theology but collect materials to write a book. I can support my family at home, at least pay the rent, and carpet the floors and send handsome sums home, too.”

He was expressing all the right thoughts to his worried sister. Yes, he could express his Christian faith, save money and provide for his family, but there was also a far more emotional reason for him to leave the United States — heartbreak.

According to Beauchamp, Griffis hesitated to leave America until he knew how his then-girlfriend, Ellen G. Johnson, felt about him. She made that clear when, instead of accepting his marriage proposal, she took an “extended” trip to Europe. Her decision “disappointed him bitterly.” With a broken heart and a promising job offer 8,000 miles away, perhaps he, too, would take his own extended trip — just in the opposite direction. The job waiting for him guaranteed a salary of $2,400, along with a “European-style home and a horse.”

A Long Journey

On Nov. 13, 1870, Griffis boarded a train in Philadelphia. For two weeks, Griffis crossed the United States, most likely ending up on America’s first Pacific Railroad, completed in 1869 and connecting Council Bluffs, Iowa to San Francisco, California. In his luggage was a Smith and Wesson revolver. This wasn’t just for his trip across the American West. Rather, Griffis had heard from several Japanese students at Rutgers that there were ongoing acts of violence perpetrated against foreigners in Japan, especially in Tokyo.

It took nearly a month for Griffis’s steamer, the Great Republic, to cross the Pacific, docking in Tokyo Bay on Dec. 29, 1870. He stayed with friend and Dutch missionary Guido Verbeck, and for six weeks learned about Japanese culture amidst a city undergoing a cultural schism. On one side was the old guard — conservative reactionaries upset over Japan’s increasingly Western-centric direction. On the other were supporters of young Emperor Meiji’s plans to modernize the country’s infrastructure. With tension came violence: “…there can now be no doubt,” wrote the New York Tribune on Jan. 27, 1871, “that [Japan] is in a state of agitation which may at any moment break out into active revolution.”

While with Verbeck in Tokyo, two Western teachers were attacked by, as Beauchamp puts it, “two sword-wielding ronins.” The teachers had mistakenly told their bodyguards to leave them that night so they could seek some “female companionship.” Both men were stabbed and cut multiple times, but survived.

To Griffis, the two teachers were at fault for being careless and unreasonable. As for Tokyo, besides being a useful base for language learning and research, Griffis saw an abundance of corruption. “It is doubtful whether vice in Edo was ever more rampant than in the third quarter of the nineteenth century…life was held to be cheaper than dirt by the swash-bucklers, ronins and other strange characters and outlaws…infesting Tokyo.”

Finally, in late February, the city of Fukui was ready to accommodate Griffis and the teacher was just fine with leaving Tokyo’s corrosive urbanity behind, imagining Fukui to be a “grand city.” But after 12 difficult days traveling by horseback for several hundred miles, Griffis was overwhelmed with “culture shock.” It was as if he’d been transported to the 12th century, a Pennsylvania Yankee in the Mikado’s court, with Fukui, as scholar Pat Barr described, “containing some 12,000 inhabitants, 2,849 homes, 25 inns and 34 streets along the center of which clear mountain water was conducted through stone channels the citizens [used to wash] their dishes and their clothes.” There was a functioning paper mill and buildings devoted to silk production, but initially Griffis was “amazed,” as he would later write in The Mikado’s Empire, “at the utter poverty of the people, the contemptible houses, and the tumble-down look of the city, as compared with the trim dwellings of an American town…I realized what a Japanese — an Asiatic city — was [and] I was disgusted.”

“It is only by keeping incessantly busy in school, at study, or at exercise…that I shall be able to drive off home-sickness and occasional dejection.” —William Elliot Griffis, July 15, 1871

Adjusting expectations

At first, Fukui officials placed Griffis in a coal-heated and Western-furnished mansion built around 1720, old enough to still have, as Griffis described to his sister, “the crest of the Tokugawa family on the lofty painted gable.” Griffis was relieved, and told that, as promised, his own Western-style house would be ready in a few months.

As for his school, Griffis reported to his sister that he was teaching inside “the very heart of an old castle” that “lies inside the innermost of the three circuits of walls and moats.” Soon, he organized his own laboratory and classroom at the college. In March, Griffis had grand ambitions, hoping to impress upon his boss that he was “more than a time-serving foreigner.” He wanted, as he stated to his sister by letter, “to make Fukuwi College the best in Japan, and to make a national text-book on Chemistry, to advocate the education of women, to abolish the drinking of sake, the wearing of swords, the promiscuous bathing of the sexes.”

Griffis, at least in the early stages, wanted to remake the culture around him, all while teaching 24 hours of classes a week via an interpreter to nearly 90 students. He kept his mind on work as best he could, determined to remain on the straight and narrow. “[It would be a] little less than madness,” he wrote to his sister at the end of March, “to bring even a brother to this land of fearful temptations and no restraints.”

By April, Griffis was bold (naïve?) enough to give Matsudaira Shungaku, the Prince of Echizen Province (Fukui being the capital), an assessment of the entire country: “We told [the Prince] that Japan could never be a great country until they honored labor, trade, the privileged classes work, educated their women, and elevated and cared for the common people. Think of it! In a despotic country, and in a Daimio’s presence, promulgating such revolutionary ideas.”

For those first few months, Griffis kept himself busy to the brink of total exhaustion, offering classes in just about any subject he’d learned back in America: History, the U.S. Constitution, bible study and physiology. By July, he wrote again to his sister how much he missed home: “It is only by keeping incessantly busy in school, at study, or at exercise…that I shall be able to drive off home-sickness and occasional dejection.”

For as much as Griffis was attempting to promote a cultural change in Fukui, he as well had started to see the Japanese people differently. As he would later write in his bestselling classic, The Mikado’s Empire, Griffis was even beginning to question the ways he’d been taught at an early age: “Why is it that we do things contrariwise to the Japanese? Are we upside down, or they? The Japanese say that we are reversed. They call our penmanship “crab-writing,” because, say they, “it goes backward.” The lines in our books cross the page like a craw-fish, instead of going downward “properly.” In a Japanese stable we find the horse’s flank where we look for his head. Japanese screws screw the other way. Their locks thrust to the left, ours to the right…A Caucasian, to injure his enemy, kills him; a Japanese kills himself to spite his foe. Which race is left-handed? Which has the negative, which the positive of truth? What is truth?”

William Elliot Griffis trip from Philadelphia to Fukui (1870-1871)

- November 13, 1870 – Left Philadelphia by train

- November 27/28, 1870 – Arrived in San Francisco

- December 1, 1870 – Boarded the Great Republic steamer, bound for Tokyo

- December 29, 1870 – Arrived in Tokyo Bay

- -Stayed with Guido Verbeck for at least five weeks, preparing for his trip to Fukui

- March 4, 1871 – Arrived in Fukui after traveling with “twelve knights on horseback.”

Source: Edward R. Beauchamp, “Griffis in Japan: The Fukui Interlude, 1871.” Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 30, No. 4, 1975, pp. 423-452.

Temptation

But a fierce loneliness started to invade his thoughts. “My saddest and sorest need is for something to love, something to caress or at least some congenial soul and presence. The temptations to a lonely man here are fearful. I dare not have an idle moment.” In August, he moved into his newly built European house, and was ordered to pay for expenses and take on a servant. The servant he chose turned out to be a 17-year-old girl whose job it was to “wait on the table, and take care of my room specially.”

Griffis was a devoted Christian, and kept nearly puritanical ideals. Sleeping with her would have been a sin. His interpreter and friend, meanwhile, had married a “blushing damsel of 15,” and moved away.

Soon, Griffis started to grow fond of the female servant. Too fond, actually. At least for him. The temptation to be with her grew so difficult that he asked her to leave. In a September letter to his sister, he writes with a touch of triumph. “In my own household, I have made another change. The young girl whom I took for a servant to wait specifically on me proved to be very faithful, diligent and pleasant in every way, anticipated my every want, and made my house almost as comfortable as a home; I like her very much. All of which to a sometimes weary and home-sick young man must necessarily be a strong temptation in his lonely hours. I found after two weeks, that she made too much comfort for me, and was too attractive herself. After having her [for] 11 days, I sent her away, before temptation turned into sin…and now, though with less comfort and a more lonely house, I can let all my inner life be known to you without shame.”

He wrote sincerely to his sister, but the truth was that he remained tempted. One also wonders why he chose, of all servants, an “attractive” 17-year-old? Had Griffis been trying to test his own resolve?

Still in September, Griffis wrote what must have been a bit more honest, descriptive and vivid letter to Guido Verbeck, still living back in Tokyo. But Verbeck, 13 years older than Griffis and a devout Christian married with children, lashed out at his good friend, pleading for him to settle down. In a manner of words, he implored Griffis to focus on his future: “Do not think of temptations!” wrote Verbeck. “If your religion does not hold you up, think of your parents & sisters, of your future wife. Put it out of the question…Nonsense! Don’t frighten a man with such mean trash! Name, influence, respect, future happiness, present peace, all would be irretrievably gone! Be a true man & Christian. Friends far & near are watching you—& so is God—no, no, you only meant to stir me up & you have done it.”

As far as has been recorded, Griffis resisted. Four months later, he left Fukui, accepting a position in Tokyo, thanks in large part to Verbeck’s help. His new position, at a college later to combine into Tokyo University, kept him in a more comfortable, less lonely state than Fukui. He spent the next 2 ½ years learning the language and the country’s history.

Legacy

In 1872, he contributed an article to the Scientific American. It’s clear from his thoughts that Griffis had come far from his first few months in Fukui, where initially he’d hoped in several ways to “save” and transform Japanese culture. “I should advise no American to come to Japan,” Griffis wrote, “unless he has a position secured before he comes. A man can do well here if he comes to Japan having been appointed in America. It gives him prestige over those who are trying to get employment here…In regard to men appointed to offices with high sounding names and large salaries [in their home country], I am afraid many people will be disappointed concerning Japan. The Japanese simply want helpers and advisors. They propose to keep the ‘bossing’, officering and the power all in their own hands…”

After leaving Japan in July 1874, he completed The Mikado’s Empire, a mammoth history of Japan combined with his own personal memories, including his time in Fukui. Griffis’s book, published in 1876, sold widely, and influenced the next generation of scholars and writers, such as Koizumi Yakumo (born Lafcadio Hearn, before becoming Japanese and changing his name).

Griffis did not return again to Japan until 1926, a year before his death. After a lifelong career of publishing books and articles about Japan, he was honored by the Emperor. As for his time in Fukui, the house where he “resisted temptation” and taught dozens of students a variety of subjects, still stands, as does a sculpture of Griffis sitting on the bench, ever ready to teach, Taro Kusakabe nearby.

This will be the last Japan Yesterday in 2021, but feel free to read the others in the series below.

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series:

Volume 2 (September 2019 – present)

- Marian Anderson sings for the Empress of Japan

- Robert Kennedy confronts communist hecklers at Waseda University in 1962

- Commodore Perry’s black ships deliver a letter to Japan in July 1853

- The story of Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s trip to Shuri Castle in 1853

- Japanese journalist witnessed the death of Malcolm X

- Muhammad Ali fights Antonio Inoki at the Nippon Budokan in 1976

- Eleanor Roosevelt visits ‘burakumin’ and Emperor Hirohito in 1953

- Charles and Anne Lindbergh fly 7,000 miles to Japan in 1931

- A young Douglas MacArthur visits Japan in 1905

- J. Robert Oppenheimer father of the atomic bomb visits post-war Japan

- Alexander Graham Bell falls asleep meeting Emperor Meiji

- Frank Lloyd Wright designs Japan’s Imperial Hotel during a midlife crisis

Volume 1 (November 2018 – May 2019)

- The ‘Sultan of Swat’ Babe Ruth visits Japan

- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

- Margaret Sanger brings 'dangerous thoughts' to Japan in 1922

- Bertrand Russell’s blinding Japanese resurrection

- Audrey Hepburn casts a spell over post-war Japan

- Ralph Ellison makes himself visible in 1950s Japan

- John Hersey visits the ruins of Hiroshima in 1946

- Russia’s Nicholas II is scarred for life in 1891 Japan

Patrick Parr’s second book, One Week in America: The 1968 Notre Dame Literary Festival and a Changing Nation, was released in March 2021 and is available through Amazon, Kinokuniya and Kobo. His previous book is The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age, now available in paperback. He teaches at Lakeland University Japan in Tokyo.

© Japan Today

7 Comments

Login to comment

u_s__reamer

The Japanese simply want helpers and advisors. They propose to keep the ‘bossing’, officering and the power all in their own hands…”

He nailed it! The Japanese were undoubtedly wise to adhere strictly to this policy, but the price to be paid was the prolongation of their insular mentality which led to the catastrophe of WW2 and the snail-pace of post-war "internationalization" that has often left them out of step culturally with the rest of the developed world.

11F

Have to hand to it him for not indulging, dudes these days are completely opposite. Mindset back then shows how different we are.

Laguna

I love this series and look forward to each and every article. Keep it up, JT!

1glenn

In the 1970s in America, inter-racial marriages were becoming common, but not so in the 1870s. For a White to bring a non-White wife (or husband) back to the States in the 19th century would have presented huge challenges. It would be educational to find out about any such marriages, and how they fared.

englisc aspyrgend

If temptation presents itself, give in quickly lest it goes away!

I am afraid Griffis attitude is all too typical of a moralising, puritanical, self righteous and dictatorial minority who have always sought to impose their barren and narrow minded morality upon others.

Travel is supposed to broaden the mind, I hope he came away a less narrow and self righteous individual, though I doubt it.

Big Yen, I agree, I think she made the right decision.

Desert Tortoise

Just to play the devil's advocate, who are we to assume that even if Mr. Griffis hormones got the better of him and he tried to initiate a relationship with this young girl that she was had any interest in him beyond her pay and sustenance?