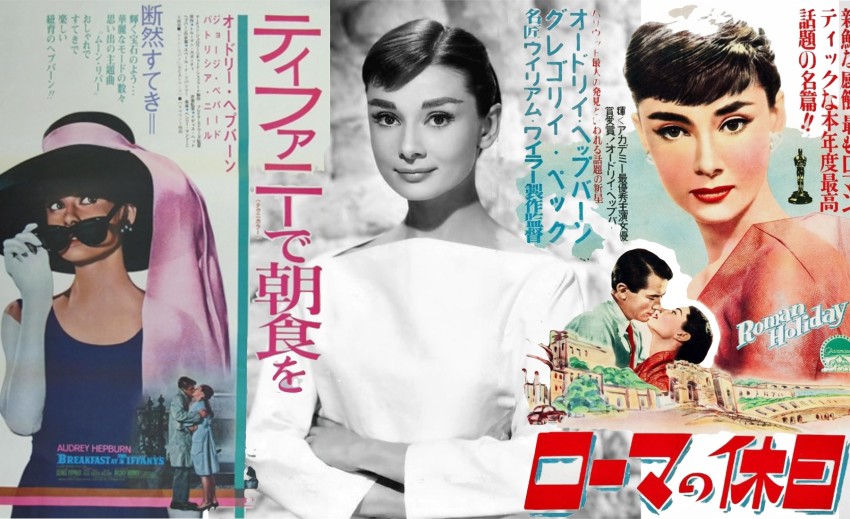

On April 19, 1954, the image of Audrey Hepburn first appeared at the Hibiya Movie Theatre. The film, "Roman Holiday"— given a five-week-run, according to scholar Zen Yipu — had just been awarded three Academy Awards, one of course for Hepburn's performance — her debut. Hollywood had never put forth a star with such a unique set of skills. Hepburn was quinti-lingual (French, Spanish, Italian, English and Dutch) with eyes that could simultaneously radiate goodness and mischief.

Yet the spell of Audrey Hepburn wasn't cast upon Japan because of her awards or language abilities. It started, quite simply, from a haircut.

The scene appears at around the hour mark of the film and, at least according to a widely circulated news article, Hepburn's drastically shortened cut and playful bangs rippled throughout the country, even if the Associated Press described the hairstyle as being created by a “run-away lawn mower.” Three months after the film’s release, Japanese film producer Masaichi Nakata confirmed the nationwide craze: “Audrey Hepburn’s pictures have captured Japan. They’ve beat out Marilyn Monroe, and the westerns — and all Tokyo girls have suddenly cut their hair.” Around the same time, the following AP story appeared in newspapers across North America:

Prayer Over Hair

Pale blue incense rose toward the gilt ceiling.

Low chanting spread through the dim temple, and a little silver bell tinkled behind the sanctuary.

Kimono-clad women knelt on the white straw mats and bowed deeply and reverently before the great golden image of Buddha.

They were the beauty parlor operators of Kyushu, asking forgiveness — for cutting off all that mountain of girls’ hair in the Audrey Hepburn mania that swept Japan’s island chain from Kushiro to Kagoshima.

In "Roman Holiday," Hepburn’s haircut is an act of rebellion against her current lifestyle: that of a princess swallowed by obligations and routine formalities. She wants to connect with the currents of society, to live within the mainstream and escape from the daily tedium that comes with being a part of a royal family.

For Japanese women in the theater that day, Hepburn's character felt relatable in a number of ways. On a surface level, Hepburn's slim, understated figure was far more familiar and imitable compared to the busty, overstated figure of another femme fatale, Marilyn Monroe, who'd just visited Japan with Joe DiMaggio several months before the release of "Roman Holiday." Hepburn's ballet-like posture and disciplined composure echoed the strict etiquette-driven upbringing of many Japanese women in 1954. In the film, when Hepburn discreetly tries to itch her foot while formally greeting various officials from around the world, a few Japanese audience members may have thought: I know exactly how she feels.

Perhaps this is all somewhat obvious. Sure, Hepburn's looks and movements are reminiscent of Japanese women but if that were the end of the spell, why then is Hepburn still — 65 years later — so lovingly embraced by Japan? The answer may lie in the way she lived her life: with grace and dignity.

Hepburn may have worked with Hollywood, but she was far from American and her turbulent upbringing was anything but charmed, despite being raised by a mother of Dutch nobility. Similar to many of the twenty-three-year-old Japanese women watching "Roman Holiday," Hepburn grew up enduring the rationed hardships of World War II, becoming malnourished during the five-year Nazi occupation of the Netherlands and surviving, according to biographer Alexander Walker, on one meal a day “of watery soup made from wild cress and herbs” and a bread-ish material of “mashed pea-pods allowed to set in a jelly-mould.”

Hepburn also lived through the Nazi-execution of her uncle and while stuck in Arnhem, according to biographer Barry Paris, she witnessed murder firsthand. “We saw young men put against the wall and shot,” Hepburn recalled years later. “And they’d close the street and then open it, and you could pass by again… Don’t discount anything awful you hear or read about the Nazis. It’s worse than you could ever imagine.”

When watching Audrey Hepburn in a film or even during an interview, there always seems to be a poetic restraint to her character, as if, through her experiences in war-torn Netherlands and her subsequent ballet training in England, she created a tightened circle of grace and elegance to which no one could have access except herself. This inner refined core has not been forgotten in Japan.

To illustrate this, look no further than an article published in Switzerland in 2001. In Tolochenaz, a Swiss village near Lake Geneva, thousands of tourists visited what is called the Audrey Hepburn Pavilion, a museum dedicated to her memory. Out of all the visitors, “70 percent… come from Japan.” As Franca Price, the then-director of the museum, put it, “From the time she appeared in "Roman Holiday," she was Japan's favorite actress. And she remains Japan's favorite actress. The Japanese are devoted to Audrey Hepburn. For them, she is the epitome of beauty, simplicity and absolute purity." The museum closed in 2002, due mainly to the disapproval of Hepburn’s sons, who believed it over sensationalized the memory of their mother, but Hepburn’s Tolochenaz tomb (Hepburn passed away in 1994) is still visited by Japanese tourists to this day.

“Giving is living. If you stop wanting to give, there’s nothing more to live for.” ~Audrey Hepburn

Two years after "Roman Holiday’s"success, another film, "Sayonara," came onto Hepburn’s radar. Hollywood producers, aware of Hepburn’s growing fame in Japan, considered her for the lead role. This meant that Hepburn would indeed be acting Japanese. At this moment, Hepburn’s modesty took center stage, keeping her from making what may have been a big mistake: “I couldn’t possibly play an Oriental. No one would believe me,” she told director Joshua Logan. “They’d laugh. ['Sayonara'] is a lovely script. I’m longing to see it, and I would love to play it, but I can’t… I don’t think anyone could persuade me to. I know what I can or can’t do. And if you did persuade me, you would regret it, because I would be terrible.” (The part eventually went to newly discovered Japanese American actress Miiko Taka who starred opposite Marlon Brando in the 1957 film.)

After her other style-changing role in "Breakfast at Tiffany’s," Hepburn started to slowly extract herself from the Hollywood spotlight. It wasn’t until 1983 that Hepburn stepped foot on Japanese soil.

Givenchy and Hepburn

In late March 1983, Audrey Hepburn and her two sons (13-year-old Luca and 23-year-old Sean) flew to Japan to celebrate the 30-year anniversary of the Givenchy brand. Hubert de Givenchy and Hepburn had been working together since the 1954 film "Sabrina," and over the years, as Givenchy himself would later admit to the New York Times’ Dana Thomas, “the results were extraordinary because her face and her style became my style.” One such collaboration is Hepburn’s now-iconic black dress in "Breakfast at Tiffany’s."

Prior to making eight appearances over a two-week span that culminated with a main Givenchy fashion show on April 13, Hepburn and Luca stayed at the historic Nara Hotel in late March for three nights, the same hotel where Albert Einstein played piano during his December 1922 visit. While there, Hepburn mainly stayed in since Luca had a fever, so she adored a black chandelier with hanging lanterns and appreciated the hotel’s serenity, calling it “beautiful and wonderful.”

UNICEF

After appearing at an international music festival fundraiser for UNICEF in Macau, China, the success of it caused Hepburn to become more involved in events to help the organization. As former UNICEF chief Christa Roth recalled: “We didn’t go to her. She came to us.” They targeted a date that would have a maximum financial impact for UNICEF and, lo and behold, the World Philharmonic Orchestra “was embarking on an enormous global tour,” and one of their dates was in Tokyo in early March 1988. "We knew Audrey had an enormous following among the Japanese,” Roth continued. “We all decided she should appear there on our behalf, introducing the orchestra and speaking about our work. The numbers who attended exceeded our wildest expectations. It was like a national event.”

Roth later reflected on Hepburn’s actual presence in Japan. “It was mind-boggling. In Tokyo we organized a press conference in a normal hotel room. We thought maybe a few journalists would come, but there were tenfold — we had to change rooms to accommodate them all.” The enormity of Hepburn’s presence was life-changing. “I think that experience [in Japan] decided Audrey: if she could lend her name and fame to UNICEF in such a way that it would help our work with children, she would. That was the beginning; that was how it all started. No one could have foreseen what it led to."

Indeed, soon after her successful appearance in Tokyo, Hepburn was named a Special UNICEF Ambassador, traveling to Africa and countries such as India to help impoverished children.

The Gardens of the World

Her travels with UNICEF became so numerous near the end of her life that it is difficult to know how often Hepburn traveled to Japan, but her last well-documented trip involved shooting an eight-episode docuseries in 1990, titled "Gardens of the World." In the seventh episode, Hepburn visited a variety of Japanese gardens, one of her favorites being Kyoto’s Saiho-ji, a moss temple that Hepburn describes as “an enchanted world of shades of green.” The program was ideal for what had become for Hepburn a minimalist lifestyle in Switzerland, as she mainly relaxed at her home, listened to music and tended to, according to Barry Paris, “a fruit-producing orchard and extensive vegetable and flower tracts.”

By the end of her life, over 50 books had been published in Japanese with her as the main subject. Robert Wolders, her longtime partner, recalled the reaction she’d receive whenever they visited Tokyo. “We used to go to Japan quite often for UNICEF, and Audrey couldn’t go out because people would swoon on the sidewalk.” Hepburn, according to Donald Spoto, donated the entirety of her "Gardens" paycheck to UNICEF. In what could be considered her life mantra, Hepburn very often put others before herself. “Giving is living,” she once said around this time. “If you stop wanting to give, there’s nothing more to live for.”

On Jan. 20, 1993, Hepburn succumbed to colon cancer at the age of 63, a day before "Gardens of the World" premiered in the United States. While she is still actively remembered around the world, her deepest societal imprint may very well end up being Japan. In January 2018, 25 years after her death, an Audrey Hepburn photo exhibition was put together at a Mitsukoshi department store in Nihonbashi, traveling to other locations as well, such as Yokohama. To many Japanese women, the name Audrey Hepburn, or 永遠の妖精 (“eternal fairy”), will continue to be a symbol of a life well-lived and one filled with beauty both inside and out.

Next month we'll look at author Ralph Ellison's 1957 trip to Japan, five years after the release of his classic American novel, "Invisible Man."

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series:

-- Bertrand Russell’s blinding Japanese resurrection

-- Birth control advocate Margaret Sanger brings 'dangerous thoughts' to Japan in 1922

-- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

-- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

-- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

-- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

-- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

-- The Sultan of Swat Babe Ruth visits Japan

Patrick Parr is the author of “The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age.” His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Politico and The Boston Globe, among others.

© Japan Today

4 Comments

Login to comment

alfconde

Great Article! I have lived the past 27 years in Japan and witnessing the similarities of Japanese women so close to Audrey Hepburn... with grace and dignity. The very difference is Audrey speaks expressing beauty, love and empathy while most Japanese don't, but are very polite though. If only Japanese ladies are equally treated then it's another story.

1glenn

"A life well lived." Is there any higher praise?

1glenn

I am impressed with the honesty and accuracy of her statement describing the Nazis. "It's worse (the Nazis) than you could ever imagine."

I will never forget my dad's description of his time fighting the Nazis. He said something similar; that whatever you read, whatever you see in a movie, it was worse. The horrors of fascism were worse than we can imagine.

It is truly shocking that we just had a president who described anti-fascists as bad people. It wasn't that long ago that anyone who wasn't anti-fascist would have been publicly criticized, instead of praised.