You’d be surprised at the number of famous people in history who’ve visited Japan over the last 150 years — notable figures you might not think had ever been here. In our monthly history series Japan Yesterday, we’ll introduce times when notable figures visited Japan for the first time and what they thought of the country. You’ll meet people like Ulysses S Grant, Helen Keller, Albert Einstein, Ralph Ellison and Babe Ruth among others. In our next installment of the series, we take a look at Charlie Chaplin.

Several days before their ship, the Suwa Maru, arrived in Japan, Charles “Charlie” Chaplin and his brother and business manager, Sydney, wanted to prepare themselves for what they were about to experience. The Japanese crew, happy to oblige, prepared a formal Japanese meal and setting. According to “Syd Chaplin: A Biography” by Lisa K. Stein, for “two solid hours,” Charlie and Sydney sat in a standard seiza (traditional Japanese sitting by kneeling with the tops of the feet flat on the floor and sitting on the soles) position wearing traditional Japanese garb. The crew cooked an assortment of dishes and after struggling to grab single peas with chopsticks, the brothers eventually finished the meal, their legs a twisted mess. Sydney later compared their “aches and cramps on rising from a squat” to “the feeling after a first day’s horseback riding.”

On May 14, 1932, Chaplin landed in Kobe to a crowd of thousands. As recounted in both his 1933 memoir “A Comedian Sees the World” and 1964’s “My Autobiography,” his reasons for visiting Japan for the first time were two-fold. From a business standpoint, Chaplin hoped to book a few locations and promote his film, “City Lights,” released in 1931. More purely, however, he’d been enamored with Japan ever since a Japanese kengeki (samurai drama) theater group had performed in Los Angeles two years earlier. As he watched the intense, choreographed chambara (sword fighting), Chaplin soon reminded himself of other aspects of Japanese culture he’d read about and admired. Like thousands of others during the early part of the 20th century, Chaplin had been introduced to the country through the evocative writings of Lafcadio Hearn. He wrote in his 1964 memoir: “[Japan] has always stirred my imagination — the land of cherry blossoms, the chrysanthemum, and its people in silk kimonos…”

His trip started stirringly enough. Along the docks were thousands of “Little Tramp” fans who’d come to know him through his work in silent films such as “The Kid” (1921) and “The Gold Rush” (1925). Chaplin’s silent films also required a very minimal amount of English to be understood. As he stepped off the boat, airplanes flew by at a low altitude throwing out “pamphlets of welcome.”

Besides his brother, Chaplin was also accompanied through Japan by his longtime assistant, Toraichi Kono, who grew up in Japan before settling in southern California and meeting the comic actor in 1916. The importance of their friendship has been a topic of debate by Chaplin scholars ever since a Kyoto conference in 2006, but it’s safe to state that Kono, who also acted in Chaplin’s 1917 film “The Adventurer,” would be Chaplin’s main guide during their three-week trip.

As soon as they arrived, Kono started hearing murmurs of political unrest. The current prime minister, Tsuyoshi Inukai, was in a volatile position of promoting peace and compromise with China while the Japanese military had laid claim to Manchuria in 1931. For the five months Inukai had been prime minister, the country’s civilian government and military remained split in the way they saw Japan’s future. With this division slowly coming to a boil, Kono advised Chaplin to obey as many of the national customs as they could.

Swiftly, the three men, escorted by a large group of policemen, went by train to the Imperial Palace, “where we conformed to the Japanese custom and paused before the gates to pay our respects, then on again to the hotel.” Somewhat unaware of why they were bowing, Chaplin later learned from Kono that it was a gesture of courtesy and respect, especially toward militarily-connected groups of uyoku dantai (ultranationalists) eager to overthrow the government — groups somewhat similar in tone and agenda to many of today’s “black trucks” that drive around cities and towns blaring right-wing propaganda on Japanese national holidays.

Soon after paying their respects at the Imperial Palace, Chaplin, Sydney and Kono went to a restaurant that night for dinner. They had their own private room, but during their meal six young men entered, one of them sitting next to Kono. These young men had been threatening Kono ever since he arrived in Japan. Earlier in the day, one of the men had asked Kono to ask Chaplin if the actor would look at a few "pornographic pictures painted on silk… at his house." Chaplin emphatically said no, but now here was the same man, "arms crossed," muttering threats into Kono's ears. In his autobiography, Chaplin wrote that “Kono, without looking up from his plate, mumbled: 'He says you've insulted his ancestors by refusing to see his pictures.’” Kono was petrified, but Chaplin, after hearing Kono's translation, was annoyed enough to put his hand in his coat pocket and shape it as if it were a gun: "What's the meaning of this?" he shouted at the men while standing.

They paid their bill and left the restaurant without any more confrontation.

The next morning, May 15, Chaplin woke to find “a cartload of presents and stacks of mail.” At least from Chaplin’s perspective, he appeared welcome by most of the country, but according to Sydney and Kono, they were all “being watched… I must admit that Kono was looking worried and harassed every hour.”

“Chaplin is a popular figure in the United States and the darling of the capitalist class. We believed that killing him would cause a war with America.” – Lieutenant Seishi Koga, 1932

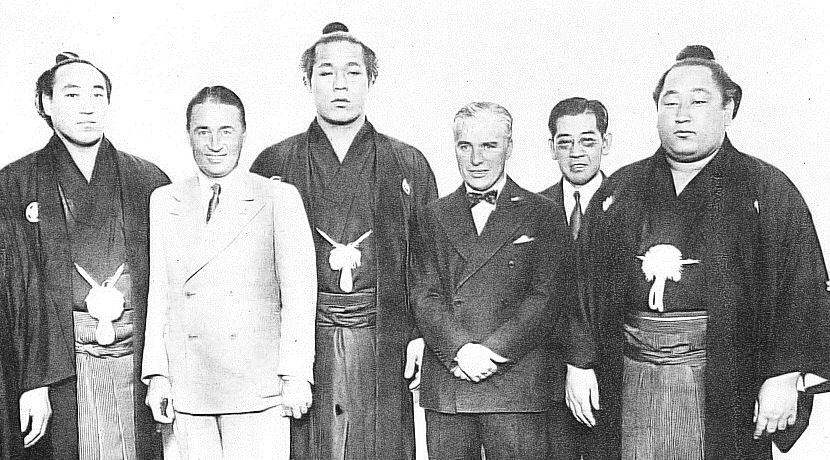

That same morning, the prime minister's son, Takeru Inukai, or "Ken," called Chaplin's hotel and arranged for the group to watch a few sumo wrestling matches. As Inukai organized the seating at the stadium, his father's security was ambushed by an ultranationalist organization called the Kokuryukai (Black Dragon Society). As the young men (several of whom may have been at the restaurant attempting to strong arm Chaplin) pointed their guns at the prime minister, Chaplin sat comfortably in a box seat, thinking that sumo was "amusing to watch… if you don't understand the technique, the whole procedure looks comic. Nevertheless, the effect is hypnotic and thrilling."

Back at the Inukai home, the prime minister calmly asked the men to not murder him in front of his wife and daughter. They complied and within the hour, Takeru was notified by a man of what had occurred at his home. After briefly leaving the box, Takeru came back and appeared devastated. Chaplin noticed immediately: "I asked him if he were ill. He shook his head, then suddenly covered his face with his hands. 'My father has just been assassinated,' he said."

According to Gerith Von Ulm’s 1940 biography, "Charlie Chaplin: King of Tragedy," the group left the sumo stadium and headed back to the hotel. The Black Dragon Society not only killed the prime minister, but also attacked the home of a past minister of foreign affairs and attempted to bomb several banks in Tokyo in the hopes of crippling the economy enough to start a revolution. With the chaos still ongoing, Chaplin offered brandy to a grieving Takeru. After the killers had completed their attack and turned themselves in to the police, Chaplin and everyone else went over to the prime minister's home. Chaplin saw that "the stain of a large pool of blood was still wet on the matting."

There was too much pandemonium at the time for Chaplin to understand how closely he'd been targeted by the far right-wing group, but his brother Sydney soon connected the tense moment at the restaurant with the murder, and this realization lingered in Chaplin’s mind for years. One thing Chaplin clearly understood on May 15 was that Takeru would have been killed had he not been down at the stadium arranging Chaplin's sumo attendance. It was only after Chaplin read Hugh Byas's 1942 book, “Government by Assassination,” that he learned one of the leaders of the attempted coup d'etat, Seishi Koga, brought up the idea of killing him during his trial. According to the book, Koga had said: “Chaplin is a popular figure in the United States and the darling of the capitalist class. We believed that killing him would cause a war with America.” Koga's goals were plain: They wanted to "overthrow the very centre of government” and create enough havoc that only the military could obtain law and order. Their coup had failed, but the amount of public support shown toward their fates delivered a light sentence and a foreshadowing of what was soon to come.

From Chaplin's perspective, writing many years later, it was humorous to think the men didn't know he was British: “I can imagine the assassins having carried out their plan, then discovering that I was not an American but an Englishman — ‘Oh so sorry!’”

Despite this close call, Chaplin did salvage his first trip to Japan. Before leaving for America on June 2, he watched a series of kabuki (Japanese classical drama) performances. In both of his memoirs, Chaplin describes what he saw in elegant detail — a master actor joyfully analyzing an art form he held in high regard. “I saw what was comparable to ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ a drama of two young lovers whose marriage is opposed by their parents. It was performed on a revolving stage… , which the Japanese have used for three hundred years." After their parents forbid the romance, "the lovers decide to commit suicide in the traditional Japanese way, each one bestrewing a carpet of flower petals upon which to die; the bridegroom to kill his bride first, then to fall upon his sword."

While absorbing kabuki on a near nightly basis, Chaplin also had a chance to experience a traditional tea ceremony, one of the highlights of the trip: “More than anything I saw in Japan, the tea ceremony revealed to me the character and soul of the nation — perhaps not of modern Japan, but the Japan of yesterday. It exemplifies the philosophy of life, beautifying the simple action of preparing tea to please the senses, utilizing an everyday fact to express the art of living.”

When Chaplin returned to the United States in June 1932, he’d felt a change in the air after being gone for nearly a year. During this time, the Great Depression continued to decimate the workforce and Chaplin had trouble measuring it: “Something has happened to America since I’ve been away. That youthful spirit born of prosperity and success has worn off and in its place there are a maturity and sobriety… ” Traveling from Seattle to Hollywood… “it seems impossible to believe ten million people wanting when so much real wealth is evident.”

Decades later, while living in Vevey, Switzerland, Chaplin reflected on his time in Japan. He would go on to visit the country three more times in his life but, writing in the early 1960s, he’d grown doubtful of the country's cultural future: “How long Japan will survive the virus of Western civilization is a moot question. Her people's appreciation of those simple moments in life so characteristic of their culture — a lingering look at a moonbeam, a pilgrimage to view cherry blossoms, the quiet meditation of the tea ceremony — seems destined to disappear in the smog of Western enterprise.”

Next month we’ll go back 64 years, to the time Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio, for better or worse, honeymooned in Tokyo.

The first part of this series features Albert Einstein's visit to Japan after he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1922.

Patrick Parr is the author of “The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age.” His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Politico and The Boston Globe, among others.

© Japan Today

5 Comments

Login to comment

Laguna

Mr. Parr, your writing style is elegant and the content fascinating. JT, thank you for this series. I look forward to more and hope each successive article contains links to all the previous for fear I may have missed one.

Toasted Heretic

Fascinating article. And a mention for Lafcadio, as well.

Thanks, Patrick Parr & JT.

Ed Woodlake

Such an interesting series, thank you. Nice to learn something new about a great legendary actor!

Nippori Nick

A very interesting story. Turbulent times indeed.

As least there are still pilgrimages (of a sort) to view cherry blossoms

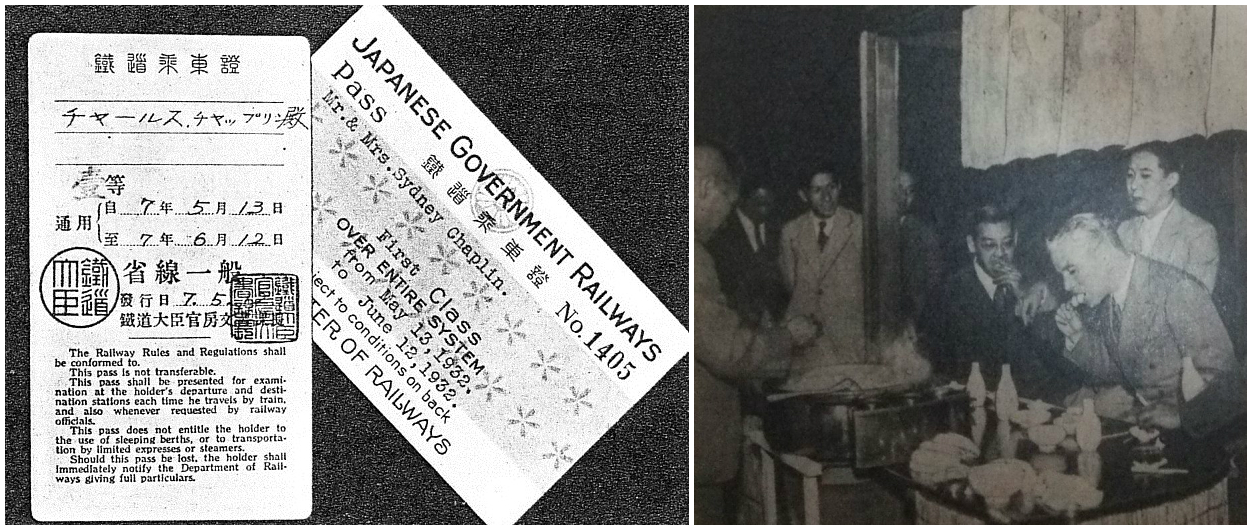

PS-Is that the Original JR pass Chaplin had? Ha.