On Aug. 28, 1898, Alexander Graham Bell sat down at a hotel in Boston to write to his father. It was two weeks before he, his hearing-impaired wife Mabel, their two daughters and their chauffeur, an African American named Charles F. Thompson, would begin making their way to Japan. Pre-Wright Brothers and pre-Panama Canal, their trip would take nearly five weeks. First was a transcontinental train ride from Boston to San Francisco, followed by a trip across the Pacific Ocean aboard the S.S. Coptic, stopping briefly in Honolulu before heading to Yokohama Bay. The amount of time it would take did not excite Bell in the least and he made his lack of desire known to his ailing father.

“Neither Mabel nor I care much about going but we realize that our opportunities for traveling with our children grow less every year. Elsie is over twenty years of age and Daisy more than 18. How much longer will we be able to keep them with us?”

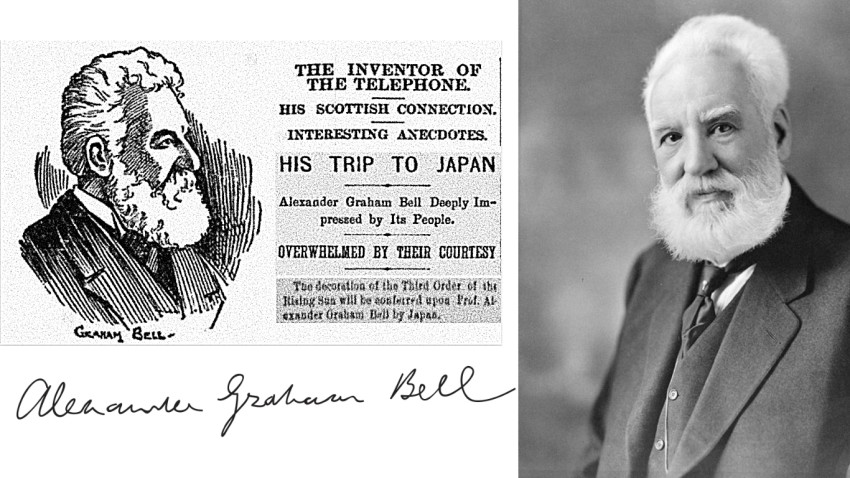

The trip would prove difficult for the 51-year-old inventor. With a long and bushy white beard accenting his 183-centimeter, 111-kilogram frame, Bell was set to stand out as a giant among Japanese residents, but the itch to travel was too strong, and since “Alec” and Mabel had lost parents (Bell’s mother, Mabel’s father) in the last year, they were also hoping to take a much-needed adventure. It didn’t hurt that Emperor Meiji had planned to bestow upon professor Bell the honor of the Third Order of the Rising Sun.

It had been just 22 years since Bell’s “speaking telegraph” breakthrough, a life-changing moment that he also shared with his father in a letter dated March 10, 1876: “This is a great day,” he wrote. “I feel that I have at last struck the solution of a great problem — and the day is coming when telegraph wires will be laid on to houses just like water or gas — and friends converse with each other without leaving home.”

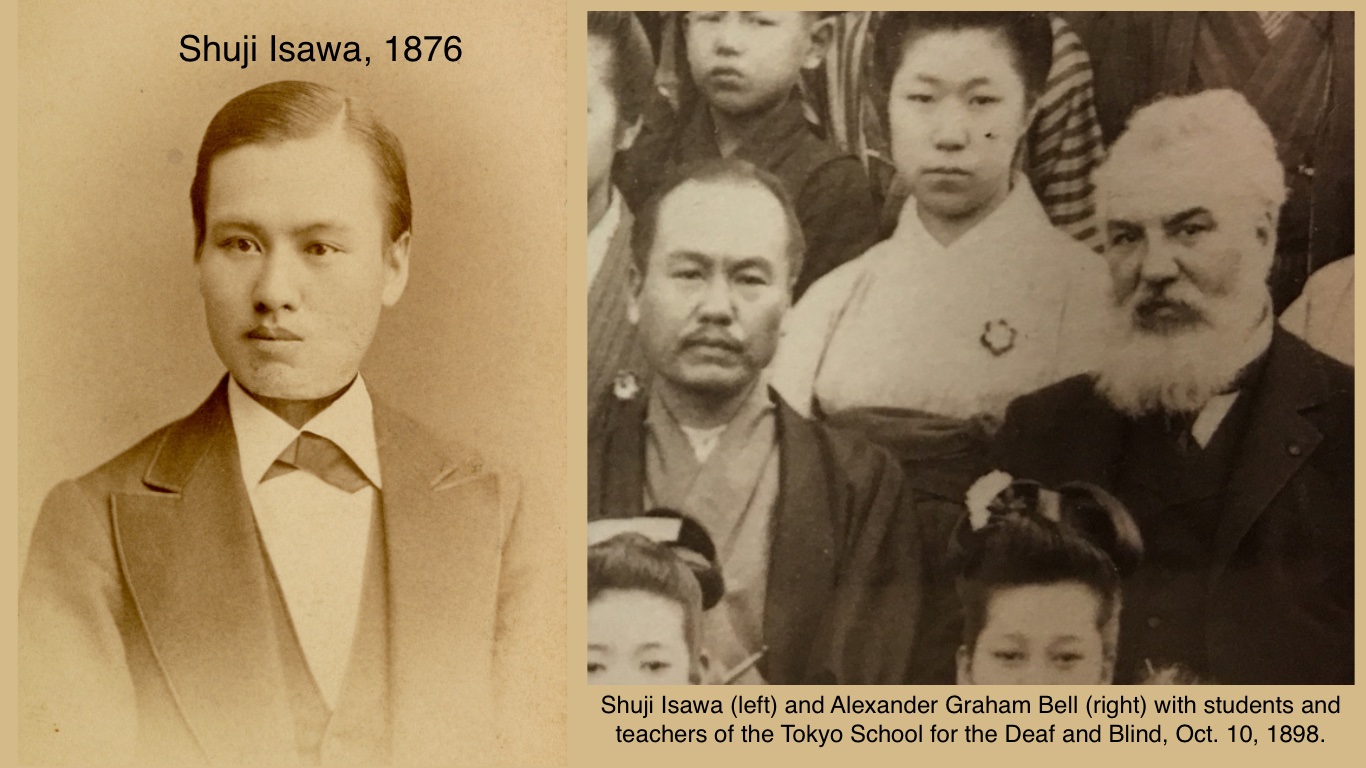

More than any other Asian country, it was Japan that first took to adopting Bell’s telephone. A small part of that reason may have been because of Shuji Isawa. As scholar Wing-Kai To described in a Kansai University paper on Jan. 20, 1877, Isawa, then a student at Bridgewater Normal School in Massachusetts (later Bridgewater State College), approached Bell and inquired about his telephone.

“Mr. Bell, will this thing talk Japanese?”

“Certainly, any language,” Bell replied.

As they experimented — Bell in one room of the building and Isawa another, an electrical wire between them — Bell let Isawa know that, yes, he did hear him, but he had no clue what Isawa had said. Fortunately, Isawa had two friends who were attending nearby Harvard College, Kanako Kentaro and Komura Jutaro, and the two young men came and had a conversation in Japanese. Thus, setting aside an undated Mohawk war cry, Japanese is considered the first “foreign language” spoken through the telephone.

News of the telephone’s invention spread quickly across the Kanto area and by the turn of the century, Tokyo had an estimated three-quarters of all telephones located in Asia. According to telephone historian Herbert Casson, Japan would later credit Bell’s invention as vital to their victory against Russia in 1905.

“Each body of Japanese troops moved forward like a silkworm, leaving behind it a glistening strand of red copper wire,” Casson wrote. This allowed troops to communicate directly with their generals as they advanced.

When looking at Bell’s childhood, one might be tempted to say that he was destined to invent such a device as a telephone. Born in Scotland in 1847, his mother was hearing impaired and as a young boy, biographer Charlotte Gray writes, he communicated with her “by speaking close to her forehead.” In quieter moments, Bell “mastered the English double-hand manual alphabet, so that he could silently spell out conversations to her.”

These inherently affectionate times may have conditioned Bell to be attracted to women in similar circumstances. Such was Mabel. As Gray wisely points out, these deep-rooted experiences caused Bell to remain “untouched by the assumption, common at the time, that somehow deafness involved intellectual disability.”

In Japan, Mabel and Bell were inseparable, by love and by circumstance. In America, they were often stared at by high society for what appeared to be public displays of affection, such as “always holding hands or linking arms because touch was such an important form of communication for them,” Gray writes. Mabel read lips, and Bell’s expressions, thanks in part to his father’s mastery of elocution, would have been very easy to follow.

Bell and the others arrived at Yokohama Bay in early October, eventually staying at the Yokohama Grand Hotel. Their schedule was packed, with trips planned in eight different cities (Nikko, Hakone, Kyoto, Osaka, Kobe, Nagasaki and Tokyo) and numerous banquets with regional chambers of commerce.

Most everyone fit in pretty well except Bell himself. His two daughters were charmed by the culture, and as Mabel took photos with a new camera, they started calling their father “Daddy-san.”

Charles Thompson, meanwhile, did not stand out. As Bell would write in 1904 while complaining to officials about Canadian hotels refusing to sell Thompson and his wife a room because of his color: “There is so little of the negro in Mr. Thompson’s appearance that he has often — in foreign countries — been taken for a Japanese, while his wife might well pass for Spanish.”

“... setting aside an undated Mohawk war cry, Japanese is considered the first ‘foreign language’ spoken through the telephone.”

By his biographers, Robert V. Bruce in particular, Bell is portrayed as “solitary and aloof.” Basic, everyday customs were often tricky because his mind was somewhere else. In Japan, this mindset created even more havoc. As his wife humorously wrote after eating at a Japanese restaurant: “Alec thinks crucifixion couldn’t be much worse than having to sit on his knees for two hours at a Japanese dinner that smelt [sic] good, but which he couldn’t get to his mouth!”

She continued, no doubt enjoying her genius husband struggle: “He had to double up [pillows] and then bow down over his knees as low as his back would allow and then try to eat off the floor. It didn’t help to see all the other Japanese guests just as comfortable as possible and have to chat and laugh while the perspiration was dropping like rain on the floor from pure agony. At present his one idea is to escape from another threatened banquet.”

Public transportation also made Bell uneasy. While in a rickshaw with Charles Thompson, he watched as his driver started to struggle from having to lug Bell’s weighty 110 kilograms. Nightmarish situations ran through his mind. A slip on a slope, followed by somersault tumbling. Thompson later recalled Bell’s words as they were transported through the streets of Japan: “I cannot get used to a man pulling me about in those terrible things, especially when I see that fellow begin to perspire.”

With Thompson, Bell felt relaxed and could express his thoughts without feeling the need to protect himself or his image. On Oct. 22, Bell was to meet Emperor Meiji. Thompson was told in advance of the details, and, as Bruce writes, the attention to detail was maddening to the inventor. First, the event would be “at ten in the morning,” a rough time for a night owl such as Bell. The inventor also needed to “appear in full evening dress, white gloves and silk hat.”

Thompson waited for Bell’s reply. At first, all he noticed was a “peculiar expression” on Bell’s face. Then, finally, a reaction: “Charles, are you kidding? Do you really mean I am to put on that horrid outfit at ten in the morning? Good Lord!”

The ceremony itself was short. Bell went through the motions, accepted his medal, then headed back to his room and “immediately went to bed without comment.” The nap would prove powerful enough for Bell to forget just exactly what he’d been through. With Thompson nearby, a drowsy Bell asked when he was supposed to head over to see Emperor Meiji.

He’d just been there, he was informed. In his stupor of sleepiness, details slowly re-entered his mind. Vaguely, he recalled Meiji as appearing superior and above all others. Bell didn’t like it, and pushed the memory back toward the fog it had originally come from. “Well,” he said before moving on, “I am glad I was not awake.”

For nearly two months, Bell and his family toured sites in Japan. According to Smithsonian researcher Robert Pontsioen, Bell was able to reconnect with his former student Shuji Isawa at the Tokyo School for the Deaf and Blind. The school was Isawa’s, having founded it three years after speaking through Bell’s telephone prototype. Not much is known of Bell’s visit that day, but he did later deliver a speech that contained the following passage, published in the Japan Daily Mail on Nov. 8, 1898:

“Dumbness comes from the fact that a child is born deaf, and that it consequently never learns how to articulate, for it is by the medium of hearing that such instruction is acquired. Put a Japanese child in America, and you find that it easily and without any apparent effort learns to speak English. Put an American child in Japan, and you will soon hear it speaking Japanese. The whole source of trouble, then, is that the ears of these unfortunates are closed. Their brains, their minds, are as fully developed or as capable of development as yours or mine.”

As for the rest of the trip, Pontsioen writes that “the Bell family toured several popular sites in the Kanto region, including the tomb of Tokugawa Ieyasu at Nikko and the hot spring resort area of Hakone, and met with American and Japanese dignitaries in Yokohama and Tokyo. They then traveled by train to Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe, and from there went by boat to Nagasaki. Finally, the Bell family returned to Tokyo via train from Kyoto in early December.”

After heading back across the Pacific on the S.S. China to San Francisco and another train trip from the west to the east coast, the Bells and Thompson finally arrived at their Washington, D.C. residence on Jan. 9, 1899, no doubt exhausted from the journey but richer from the experience. For Bell it was back to his inventions — manned kites were his fascination at the time.

For all of the trip’s minor difficulties, Bell was still able to look back at his time in Japan with joy. In a Jan. 16, 1899 interview with the D.C. Evening Star, Bell revealed as much: “I cannot begin to express my wonder and admiration at what I saw in Japan… they are the most courteous and hospitable of people.”

Bell was being diplomatic. He wanted the general public to think of Japan as a civilized society with admirable customs instead of the then-stereotype that it was a “semi-barbarous nation.” This behavior was common in Bell — a heartfelt man fighting against the heartless world. Bell even told the Evening Star reporter that a zoological park in Japan had agreed to give him six pairs of oshidori (mandarin) ducks, so that he could share their colorful beauty with a local D.C. zoo. Bell had been enamored by the elegance of the water fowl and deemed the gift a "very gracious act of courtesy."

As for Mabel, she also enjoyed the trip and it allowed her to see her husband in a different light. As she wrote to her mother during the trip: “There’s nothing like coming to Japan to find out what a big man my husband is.”

Our next installment of the Japan Yesterday series will feature architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s fascination with Japanese culture.

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series:

-- J. Robert Oppenheimer Father of the Atomic Bomb Visits Post-War Japan

-- Russia’s Nicholas II is scarred for life in 1891 Japan

-- John Hersey visits the ruins of Hiroshima in 1946

-- Ralph Ellison makes himself visible in 1950s Japan

-- Audrey Hepburn Casts a Spell Over Post-War Japan

-- Bertrand Russell’s blinding Japanese resurrection

-- Margaret Sanger brings 'dangerous thoughts' to Japan in 1922

-- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

-- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

-- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

-- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

-- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

-- The Sultan of Swat Babe Ruth Visits Japan

Patrick Parr is the author of The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age. His work has appeared in Politico, the Atlantic and American History Magazine, among others.

© Japan Today

11 Comments

Login to comment

Laguna

Thank you again. This is an erudite, informative series, and I always look forward to each new installment.

Strangerland

Very interesting article. I enjoyed it.

Alcat65

The whole, true story about the invention of the telephone needs to be told. I cannot say the article is informative, because there is no reference to Antonio Meucci, who is accredited to be the real inventor of the telephone. He submitted a patent caveat in 1871, meanwhile Bell was granted a patent in 1876. Moreover, in 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives honoured Meucci by a resolution in recognition of his work.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Meucci

gokai_wo_maneku

Great article! And five weeks from Boston to Yokohama? What a different age. It helps you appreciate all the progress. And progress from Bell's telephone to our smart phones that do everything.

Kobe White Bar Owner

Patrick Parr many thanks keep them coming please.

Fendy

Nice article! I just like to imagine what Japan may have been like back in day ...

1glenn

Thank you for the article. I think meeting the Emperor would have been very intimidating for me, but Mr. Bell was hardly awake at the time, and did not suffer much. Funny story.

Robert Pontsioen

Very interesting story - and thanks for quoting my work! If anyone is interested, my article quoted above is titled "The Alexander Graham Bell Collection of Japanese Masks at the Smithsonian" and it can be read/downloaded here:

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert_Pontsioen

albaleo

There's a lot of argument about the differences of those patents. I've read that Mecucci's patent caveat didn't describe the conversion if sound to electro-magnetic waves. But arguments like this about inventions are common - television, light bulbs, etc.

Mocheake

Excellent article. Bell seemed a lot more down to earth than I had previously imagined and much more so than some of his other contemporaries.

William Bjornson

@Alcat65

In regard to the 'invention' of the the telephone, Meucci's claim is not the only charge against Bell. Ten years after Bell's patent submission, a patent clerk testified before Congress that he was given $200 to change the time of a patent submission. Bell had filed his patent application in the afternoon of the same day that Elisha Gray had filed in the morning with an essentially identical device. The clerk testified he switched the times of application giving Bell precedence over Gray. Bell was a childhood hero but, when I learned of the corrupt way he received his fame and as a scientist, I could not forgive the fraud. Intellectual property theft, which has particularly affected women, may seem an innocuous crime but, for the victim, it is child theft.