On March 29, 1921 the Japan Advertiser of Tokyo newspaper published a report stating that British philosopher, mathematician and sociologist Bertrand Russell, at the age of 49, had died of pneumonia while teaching at a university in Beijing. There was just one minor problem with this report, however — Russell was still alive.

Yes, he was ill, but after the news had been circulated around the world, Bertrand’s brother Frank wrote a brief letter to the London Times, stating (in effect) that, “No… Bertrand is still with us, and on the mend.”

Three and a half months later, on July 17, 1921, Bertrand Russell and his pregnant, soon-to-be-second wife Dora Black stepped onto a dock in Moji, Japan. Russell hadn’t forgotten the Japanese newspaper’s premature obituary. Truthfully, in 1921, according to the Boston Globe, the erroneous Japanese journalist may have been driven by the fact that “many people in the world would be pleased to have Mr. Russell dead.”

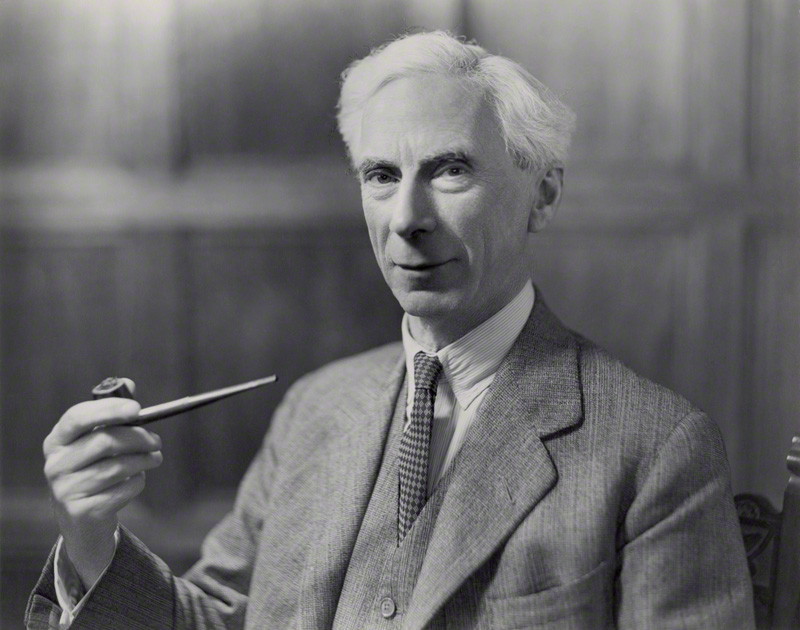

The British scholar had already achieved international renown for his breakthroughs in the field of mathematics, notably his 1910 co-authored three-volume work "Principia Mathematica," considered by scholars to be “one of the most influential books on logic ever written.”

So how could such a brilliant man be hated? Well, it started with Britain, whose involvement in World War I radicalized Russell. Soon, his anti-war protests first cost him his teaching position at Trinity College in 1916 and later landed him in jail for six months. His thoughts, consistently complex, often lost their nuance when regurgitated by mass media, and soon he’d been accused of wholeheartedly siding with Vladimir Lenin’s version of communism over the West’s “muscular capitalism.”

This was not the case. But from the moment he started living in China in 1920, he was relieved to find a far saner civilization than the Western model he’d grown accustomed to: “The Chinese are gentle, urbane, seeking only justice and freedom,” Russell once wrote, according to biographer Ray Monk. “They have a civilisation superior to ours in all that makes for human happiness… I think they are the only people in the world who quite genuinely believe that wisdom is more precious than rubies.”

However, as he too would later wonder about Japan, Russell was concerned about China becoming too Westernized, thus polluting a society that has worked and progressed for centuries without the infringement of Western force. As Monk would clearly posit: “Could the benefits of science, technology and industry be given to a society without it also importing the aggressive militarism that characterizes Western nations?”

To be clear, in 1921, Russell was unabashedly Team China and Japan knew it. In fact, prior to Russell’s July visit, the Japan Advertiser never did retract their erroneous obituary. Russell and Dora, annoyed yet amused at Japan’s actions, decided to have a bit of fun with it.

According to Russell’s autobiography, at the Moji port, Russell arrived “still feeble” with Dora by his side. The moment they stepped off the boat, “some thirty journalists were lying in wait, although we had done our best to travel secretly, and they only discovered our movements through the police. As the Japanese papers had refused to contradict the news of my death, Dora gave each of them a type-written slip…”

The sentence they had prepared made its way back to American newspapers. It read: “Mr. Bertrand Russell, having died (in Japan) three months ago, is unable to issue statements to the press.”

The journalists needed a moment to understand the joke, but once they did, according to Russell, “they drew in their breath through their teeth and said: ‘Ah! Veree funnee!’”

Russell did not particularly enjoy his 12-day trip through Japan, calling his experience “hectic… far from pleasant, though very interesting.” Much preferring the overall cultural demeanor in China, Russell felt that most “Japanese proved to be destitute of good manners, and incapable of avoiding intrusiveness.”

“Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.”

Their first stop was to Kobe to see The Japan Chronicle editor Robert Young. Along the way, Russell witnessed “a great strike going on in the [Kawasaki] dock-yards [in Kobe],” led by 33-year-old Christian pacifist and hero-to-the-poor Toyohiko Kagawa. The strike gave Russell something to smile about, since the only reason it was being allowed was due to a loophole stating that police “would not tolerate processions except in honour of distinguished foreigners.” Well, here one was, back from the dead, a momentary British zombie with sympathies toward labor unions. Russell was more than happy to discreetly slide into a labor meeting and deliver a short speech to a group of protesters. Kagawa, also an upcoming socialist politician who’d been sent to jail for his support of labor causes, hoped to use Russell’s voice to galvanize even more workers toward fairer rights for factory workers.

Young was able to escort Russell and Dora Black to Nara as well. Russell, ever ready to wax nostalgic toward cultures from bygone times, found Nara to be “a place of exquisite beauty, where Old Japan was still to be seen.” But after Nara, Kaizo magazine swooped in and took over hosting duties, leaving the couple to be “perpetually pursued by flashlights and photographed even in our sleep.”

Russell also wasn’t fond of the overenthusiastic customer service at fancy restaurants. “The waiters treated us as if we were royalty and walked backwards out of the room. We would say, ‘Damn this waiter’, and immediately hear the police typewriter clicking.” To Russell, being treated as exceptional removed him from the commonality of human experience. In reality, he was simply a cantankerous middle-aged man with his two-decades-younger second wife. Sure he’d written and read a few books, but the beauty of living was in the harmonic state of cause-sharing and togetherness.

Another aspect Russell disliked was the non-chivalrous way Japanese men treated women. In his autobiography, he called their attitude “somewhat primitive,” then recounted a moment riding a crowded “suburban train” with Dora and Eileen Power, an economic historian.

First, one Japanese man stood up and “offered his seat” to Russell, but he passed, allowing Dora to take the seat. A bit later, a second offer was extended to Russell. Once again, he deferred, urging Ms Power to take the seat. Although he could not speak Japanese, Russell could sense he’d offended the men who believed they were acting out of kindness. “The Japanese,” Russell blanket concluded, perhaps dipping into hyperbole to make his point, “were so disgusted by my unmanly conduct that there was nearly a riot.”

Russell did manage to have a few informal conversation parties with a group of around 30 professors and local intellectuals, once at the Miyako Hotel in Kyoto on July 21 and then on July 26 at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, according to scholar Miura Toshihiko. He also had a pleasant meeting with a “young and beautiful” 27-year-old progressive Japanese feminist named Noe Ito. Dora in particular enjoyed speaking to Ito, a woman whose partner was an anarchist named Sakae Osugi.

Ito and Osugi were both despised by the government and through articles, essays and demonstrations she often attempted to undermine the kokutai’s (the emperor’s sovereign government) vice-like grip over the majority’s mindset thanks in part to a series of peace preservation laws that infringed upon the right to publicly express disapproval via a labor movement or publishing. According to Russell, while he and Dora were staying with Ito, Dora asked her, “Are you not afraid the authorities will do something to you?” Ito, fluent in English, went ahead and gestured her throat being slowly slashed. “I know they will do that sooner or later,” she responded.

By the end of his trip, Russell was near his wit’s end with being photographed. After a grueling 10-hour trip “in great heat from Kyoto to Yokohama,” Russell and pregnant Dora were “received by a series of magnesium explosions, each of which made Dora jump, and increased my fear of a miscarriage.”

Back in 1923, a magnesium ribbon was used to create a flash and simulate a momentary daylight as it burned away. Line up a dozen of these cameras and have them go off simultaneously and the effect could wreak havoc on any pair of eyeballs. For Russell, it had been a long day, but the constant bombardment of flashes caused him to channel his inner barbarian. “I became blind with rage… I pursued the boys with the flashlights, but being lame, was unable to catch them, which was fortunate, as I should have certainly committed murder.”

That normally being enough description for a desperate situation, Russell, as he always did, decided to carry his own self into images of savagery. “An enterprising photographer succeeded in photographing me with my eyes blazing. I should not have known that I could have looked so completely insane… I felt at that moment the same type of passion as must have been felt by… white men surround by a rebel coloured population. I realized then that the desire to protect one’s family from injury at the hands of an alien race is probably the wildest and most passionate feeling of which man is capable.”

Still, at Keio University, Russell did have one glimmering moment. In front of an audience of 3,600, Russell pushed aside his weakened condition and gave, according to Dora, “one of [his] best lectures” on the subject “Rebuilding Civilization,” standing for over an hour despite, as writer Yamamoto Sanehiko would later report, only wanting to speak for “thirty or forty minutes…but he was so deeply moved by the enthusiasm of the large audience and forgetting about his illness…”

On July 30, Russell and Dora boarded the Empress of Asia and sailed from Yokohama to Vancouver. Despite such an arduous first trip to Japan, the philosopher would live long enough to become a fervent believer in the abolishment of nuclear weapons, a cause that united him with post-war anti-nuclear weapons groups in Japan. Soon, the Bertrand Russell Society in Japan was formed and would go on to have a successful two decades of meetings and publications. In July 1955, Russell would unite with Albert Einstein and issue the Russell-Einstein manifesto, a document sent to Congress pleading for them to “find peaceful means” to future conflicts instead of through a calamitous nuclear war:

There lies before us, if we choose, continual progress in happiness, knowledge, and wisdom. Shall we, instead, choose death, because we cannot forget our quarrels? We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new Paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.

In 1921, Russell may have stood as a way for Japan, as scholar Kondo Eizo wrote, “to understand what was going on in the world and [for Japanese intellectuals] to develop a critical viewpoint towards Japan,” but by the time he passed away in 1970 at the age of 97, he had become a grandfatherly symbol of pacifism still rarely seen today.

Next month we'll take a glimpse into Audrey Hepburn's three brief visits to Japan and why Japanese people still hold her in such high regard.

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series.

-- Birth control advocate Margaret Sanger brings 'dangerous thoughts' to Japan in 1922

-- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

-- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

-- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

-- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

-- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

-- The Sultan of Swat Babe Ruth Visits Japan

Patrick Parr is the author of “The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age.” His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Politico and The Boston Globe, among others.

© Japan Today

7 Comments

Login to comment

PerformingMonkey

One of the more interesting things I've read on JT.

Steve Martin

Interesting ... but a post-hoc prophylactic of history.

I suspect Shakespeare could use a bit of that same euphemistic resurrection .... 'Something's rotten in the state of Denmark'.

Bertie's was good in his day.

But wake me when Chomsky gets a write-up.

Wakarimasen

Yes fascinating. But also shows that for all of his brilliant insights, Russell was also quite off the mark on a lot of things.

serendipitous1

And Noe Ito along with her lover Osugi Sakae and his 6-year-old nephew would be beaten to death by the police in a police cell in September 1923, a couple of weeks after the Kanto Earthquake.

gokai_wo_maneku

Very interesting! Please, JT, more articles like this one. I also liked the other articles in this series, especially the ones on Einstein and Marilyn Monroe.

JapanFan

Mark Twain said,

“The reports of my death are greatly exaggerated.”