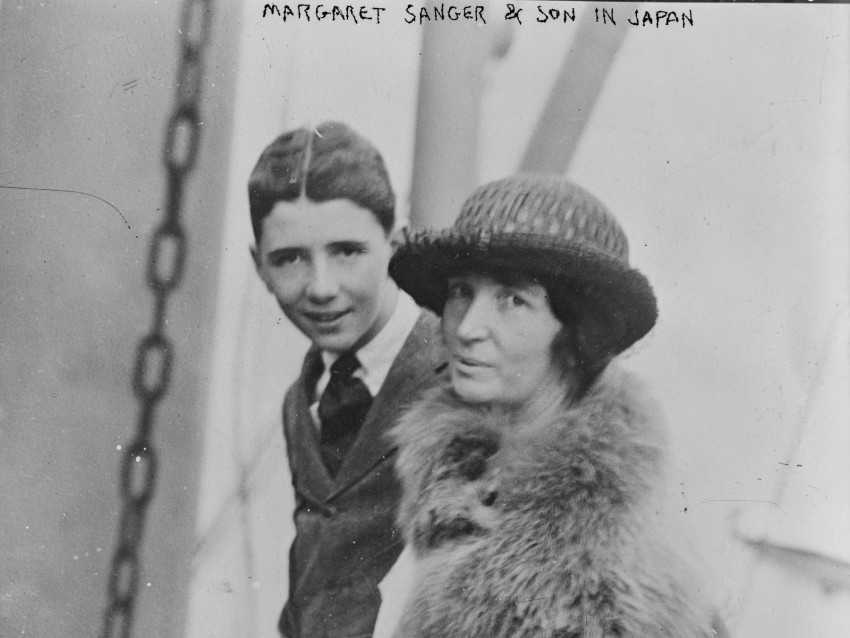

On March 10, 1922, the passenger ship Taiyo Maru docked at Yokohama Bay. On board was women's rights and birth control advocate Margaret Sanger and her 14-year-old son Grant. Her visit was sponsored by the magazine Kaizo (or “Reconstruction”). The respected publication had bankrolled a series of visits from leading Western thinkers in the early 1920s such as Albert Einstein, H.G. Wells and Bertrand Russell. Kaizo had hoped Sanger could help shed light on the much-talked about topic of the times, birth control, but the Japanese government had other ideas.

For Sanger, Japan was just the first stop on a six-month world tour, but it would prove to be her most turbulent. Still aboard the Taiyo Maru, “I was asked to make a formal request to enter Japan.” Several uncomfortable hours later she was told she could enter Japan on only one condition: "Do not deliver any public lectures about birth control."

Sanger was confused — and rightfully so. After all, the major point of her visit was to speak on this very subject, as requested by the magazine sponsoring her trip. She needed a clear reason why this restriction was being placed on her.

“It is not easy to surprise anyone who had worked for long in the Birth Control movement,” Sanger would write a few months later. “We get accustomed to the unexpected happening. In this case, however, my surprise was real, because I was led to believe by Japanese in the U.S.A. that there was a general interest in the Birth Control subject on the part of the younger members of the government.”

According to author Helen M. Hopper, the decision to block Sanger was “urged on by a large block of conservatives in the House of Peers (now the House of Councillors), the upper house of the Japanese Diet.” There were a number of reasons why the government pushed back against Sanger, and it started with the anti-immigration rhetoric coming from American newspapers and politicians stating that they were concerned with Japanese people taking over California and the entire west coast.

Because of this shadowy fear, new “alien land laws” were passed, blocking incoming Japanese immigrants from acquiring property. These fears were humiliating to a proud minority in the Japanese government. This, coupled with the recent demand by the U.S. and Great Britain for Japan to reduce its naval fleet (fearing a flare-up akin to WWI Germany), caused the government to distress over how much to trust in Western cultural ideals.

The way Sanger describes it in her autobiography, “by our Exclusion Act we had implied they were undesirable citizens, and now it was an American [myself] who was undesirable to them.”

Sanger was finally able to leave the ship after signing an agreement stating that she would avoid explaining “practical methods of contraception, suggest how to obtain birth-control literature, or introduce birth control as a method of limiting population in any public forum.” Officials would attend all of her lectures and make sure her “dangerous thoughts” were not communicated to the audience.

Fortunately for Sanger, she had three valuable resources to help spread her message to Japanese women across the country: Kaizo’s ability to adapt (how can we get around the idea of a “public lecture”?), the media’s desire to report on government controversy and, most importantly, the support of her best Japanese friend and fellow birth control advocate, 25-year-old Baroness Shidzue Ishimoto, more commonly known later as Kato Shidzue, one of the most important politicians in 20th century Japan.

Sanger stayed about one month in Japan, primarily at the upper-class home of the Ishimoto family in Tokyo. The Ishimotos had an automobile that “honked… at every turn of the wheels to squeeze through rickshaws, pedestrians, and children in the narrow, unpaved streets… ” and an old-fashioned candlestick (or upright desk stand) telephone that would begin ringing early in the morning.

This glorified home stay allowed Sanger and her son to see how Japanese people live day-to-day. Besides common differences such as using chopsticks, slippers and kneeling, Sanger in particular was impressed by what she called “the triple bow, graduated according to the social rank — an inclination, a slight pause, a deeper inclination, again a pause, and then down further until the back was nearly horizontal.” Soon her son Grant had absorbed the gesture, and “unconsciously I soon found myself returning [the bows] with equal formality.”

During the second day, Sanger went to the police to see if she could be granted more flexibility about discussing birth control to her audiences. While seated in the office, the chief of police told her with a smile that her name, “Sanger-san,” can easily be pronounced “Sangai-san” — or “destructive to production.” The group had a small laugh, and indeed the national and international press had taken up her provocative (and somewhat annoying to Sanger) nickname. But no matter how Sanger tried to convince the police, to them her ideas were “dangerous thoughts” and could upset Japan’s current social structure, even if “the density of population in tillable areas of (1920’s Japan) averaged two thousand human beings to the square mile.”

As for her lectures, they were well-attended and retitled “War and Population.” The 42-year-old Sanger gave eight public speeches, all of them from 1 p.m. to 6 p.m. Standing for five hours “was a frightful strain. The lecture with interpretations took three hours, although I could have delivered it in one, and questions took two more [hours].”

Thanks to Shidzue Ishimoto’s networking via her prosperous Minerva Yarn Shop business and Kaizo’s connection base, Sanger was able to set up private meetings with doctors and share birth control techniques. It was in Yokohama that she learned how one Japanese doctor had helped prevent pregnancy. "Dr. Kaji told [me] of the methods of [birth control] he found successful — plain soft Japanese paper folded & inserted against cervix — then as this absorbs the sperm it is removed & a clean piece wet in antiseptic solution & wiped the vagina dry & clean. 1000 cases no failures." Later, however, when Sanger introduced her version of a “pessary,” what could now be thought of as a vaginal diaphragm, she was told by a female doctor that they “caused irritation.”

"We are confident that no government will allow [Margaret Sanger] to carry on such propaganda for some time to come. Even in the United States, which takes pride in the freedom of the people in the expression of their views and opinions, she is looked upon as a sort of 'undesirable' person. Perhaps our [Japanese] authorities are taking the same view." ~Chuo Editorial, 1922.

If you are wondering about the actual birth control pill, well… that would need to wait another 77 years before the Japanese government allowed for its legal distribution. Perhaps you're thinking this leap forward was due to the advancement of women's rights across the Western world and the increasing number of female politicians. That may have been a small factor, but the straw that broke the camel's back was Viagra. Immediately deemed okay by the predominantly male government, a strong minority of Japanese women (then 102-year-old Kato Shidzue among them and still going strong) spotlighted the obvious policy contradiction. If men can take a pill to have more sex, why can't women have a pill to control the result? Thus, in 1999, the birth control pill was passed by the Diet, but to this day lags far behind condoms as the preferred contraceptive in Japan.

Sanger never did have enough patience or time to convince Japanese women of her outlook. Just before the end of her trip, she showed her frustration in writing that “the women here are too low-voiced to ever do anything. They are trying too hard 'to be or not to be' proper. One hears much of the 'New Woman' but one seldom sees her."

In the end, Margaret Sanger’s visit to Japan was good for one reason — it helped establish Shidzue Ishimoto as a leading voice for birth control and family planning. According to Hopper’s biography "Kato Shidzue: A Japanese Feminist," Sanger “was a godsend [for Ishimoto], a morale builder, an inspiration with practical advice and materials for advancing her common cause."

It cannot be exaggerated how strong the friendship was between Shidzue and Margaret Sanger. Near the end of Sanger’s life, she left very specific instructions as to how to dispose of her body. In her will, she wanted her heart to be taken from her body and “buried in Tokyo — any place the govt. or health and Welfare Ministry together with Senator Shidzue Kato wish to have it buried, as it is or in ashes.”

▼ Go to 7:44 of this video to see Kato Shidzue speaking.

Perhaps, it’s true that Sanger did not have the necessary determination to get through to the Japanese general public. She did, however, have a kindred spirit and disciple in Kato Shidzue, who in April 1946 joined 38 other women elected to the Diet, becoming a leading voice on issues such as the ending of legal prostitution in 1956 and helping women to be given fairer representation in court during divorce proceedings. Kato, who lived the entirety of the 20th century before passing in 2001 at the age of 104, helped found the Japan Family Planning Association in 1954, the closest organization in Japan connected to Planned Parenthood. Without Kato Shidzue’s groundbreaking life, Margaret Sanger’s 1922 visit would have been nothing more than a momentary spark in the darkness.

Next month we’ll look at British philosopher Bertrand Russell’s 1922 trip to Japan when he attempted to explain his controversial view of pacifism to a conflicted audience.

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series.

-- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

-- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

-- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

-- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

-- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

-- The Sultan of Swat Babe Ruth Visits Japan

Patrick Parr is the author of “The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age.” His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Politico and The Boston Globe, among others.

© Japan Today

11 Comments

Login to comment

Kenji Fujimori

Great Article JT

Toasted Heretic

Fascinating article & extremely interesting historical figure. Many thanks for this.

garypen

Birth control pills weren't legal in Japan until 1999? Amazing.

1glenn

It is amazing to think that women did not get access to The Pill in Japan until 1999.

Some more interesting dates, relative to when women got the right to vote:

1945, Japan, France, and Italy, women get the vote

1948, South Korea and Belgium

1952, Greece

1953, Mexico

1962, Monaco, Australia (indigenous peoples)

1971, Switzerland

1976, Portugal

2015, Saudi Arabia

When my mother was born, women in the USA did not yet have the right to vote in national elections.

cleo

I find that more than amazing. In the late 1970s I went to the local 婦人科, told the doc I needed contraception, he told me the pill was my best bet and wrote out a prescription for me straight away. No problem at all, just a quick blood test (if I remember rightly) and a few basic questions about general health.

When people say they 'weren't legal', do they mean not available over the counter?

GyGene

Oh me, just when I've been saying Japan needs more BABIES! The current people shortage in Japan is a desperate situation.

Khuniri

It is a matter of modernist dogma that separating sex from procreation is an absolutely good thing and that Margaret Sanger is thus a secular saint. Well, she wasn't. She was not primarily concerned with making women's lives easier (or more fun). She was first and foremost focused on eugenics, and though the term "racist" has come to be used much too carelessly, the label clearly applies to her. Today's "liberals" consistently whitewash--as it were--MS...

Serrano

Fascinating article. More articles like this, please.

"The current people shortage in Japan is a desperate situation."

There's no shortage of people on the trains weekday mornings.

MASSWIPE

When people say they 'weren't legal', do they mean not available over the counter?

Cleo: No, it's more complicated than that. Until the year 1999, the so-called "low-dose" birth control pill was not legally obtainable in Japan, either by prescription or OTC. Chances are pretty good that in the 1970s you were prescribed a high-dosage pill (approved in 1966) ostensibly designed for treating menstrual disorders. But apparently Japanese doctors went ahead and prescribed it as a birth control pill as well, although it appears they weren't supposed to that. I'm guessing many Japanese women found the side effects objectionable. Here's an article from 1999 with the details: http://articles.latimes.com/1999/jun/03/news/mn-43662

cleo

That's very interesting Masswipe, thank you for the link. Maybe I was on a high-dosage pill. No side effects, luckily.

It's funny because when I was younger (just out of uni) I was given the pill in the UK for menstrual problems, and when I came to Japan I was told I couldn't have/didn't need the pill. The doctor gave me a series of painful injections instead (which had limited effect)...and then tried to give me advice on IUD/condom use even though at the time I made it clear that I had no need for contraception.