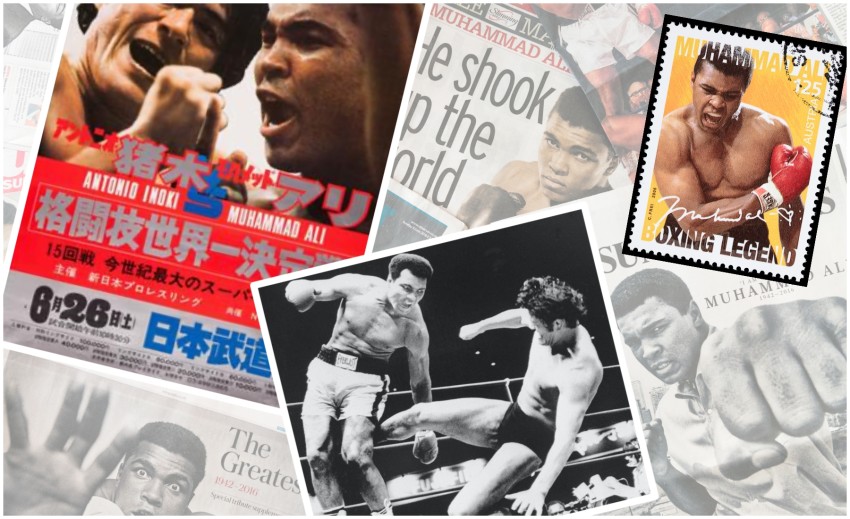

On June 26, 1976, the 14,500 ticket holders seated in the Nippon Budokan arena in Tokyo were about to become profoundly disappointed. For those who’d bought ringside seats for ¥300,000 at the time (about U.S.$1,000—or $4,500 in today’s dollars) and those in the nosebleed sections who’d forked over $17 to see two shirtless blurs tussle, the fight was supposed to be an electric, never-before-attempted affair. On one side was the most famous name in boxing, 34-year-old Muhammad Ali, eight-months removed from surviving 440 punches against Joe Frazier in the classic war-of-attrition bout dubbed the “Thrilla in Manila.” His opponent would be 33-year-old Antonio Inoki, Japan’s most popular professional wrestler. Because of Inoki’s massive chin, Ali nicknamed him “The Pelican.”

Ali and his team arrived in Tokyo on Wednesday, June 16. According to Josh Gross’s informative and entertaining book, "Ali vs. Inoki," “hundreds of fans greeted The Greatest as he deplaned” at Haneda International Airport. Far more interesting than the actual fight was the build up to it, and as soon as Ali and wrestler Freddie Blassie had cameras and microphones around them, the talking started. “We’ll kill him,” shouted Blassie. “Annihilate that pencil-neck geek. He’s got a neck like a stack of dimes. Like all the rest of you geeks out there. Look at them all. Show ‘em that right hand, champ. That’s the one!” Then Ali with the counter. “When I hit him with that it’s all over. It will all be over.” Blassie, a WWE legend, knew how to push the boundaries and made sure they’d grab a few newspaper headlines. “Take out insurance on Inoki… Big funeral for Inoki! Extra! Extra! Read all about it: Inoki sinks. Pearl Harbor, he’s through!”

For the next 10 days, Ali stayed in a seven-bedroom suite on the 44th floor of the Keio Plaza Hotel in Chiyoda, his 37-member team enjoying the luxury of having all of their expenses paid by Inoki’s promotional company. Perhaps the only deprivation for Ali was the single English-language television station.

This wasn’t the first time Ali had visited Japan. Four years earlier, on April 1, 1972, Ali had fought inside the Budokan, going 15 rounds with Mac Foster. At that time, Ali was working his way back into shape in preparation to fight Frazier for the second time. If you watch the fight, you’ll notice that it seems Ali is merely going through the motions. In newspapers, fans felt as if the fight had been some cruel April Fools Joke. Other less-informed fans were confused about Ali’s name, since the Japanese media had been promoting the fight using Ali’s name before his 1964 conversion to Islam—Cassius Clay. Regardless, hecklers were desperate for some action by the 15th round. “Either guy—fall down or fall over!” one man shouted.

Now Ali was once again at the top of the boxing pyramid. He still had difficult opponents ahead of him, such as Ken Norton, but his Manilla classic with Joe Frazier was in a way the zenith of his illustrious career. By 1976, his quick reflexes had begun to slow, as had his ability to talk in general. Although he would not be diagnosed with Parkinson’s until 1984, his rate of speech had slowed considerably. In a landmark study by Arizona State scholars and the help of Ali biographer Jonathan Eig, Ali’s speaking rate was analyzed between the years 1968 to 1981, and a clear decline was discovered.

Nothing, however, was stopping Ali from promoting one of the most unique sporting mash-ups of the 20th century. As Gross describes in his book, the fight was largely Inoki’s idea, as he attempted to broaden his global reputation by fighting the most popular boxer in the world. Inoki would wrestle and Ali would box. That was the hook, at least. Specifics would be the problem.

As the day of the fight drew nearer, however, it became evident that neither camp had thought through the official rules for the fight, nor did they wish to provide any concrete details to the general public. Simply put, Ali wanted everyone to know that this would be real, not staged as many wrestling matches were. Ali was here to knock out Inoki and Inoki was hoping to pin Ali, one-two-three.

At their weigh in the day before the fight, Ali continued to talk as a silent Inoki, who understood far more English than he let on, smiled smugly, choosing to ignore the champ’s words: “I’ll see you tomorrow.”

Ali said to Inoki: “Be serious tomorrow. Be serious. You’re meeting Muhammad Ali. The gloves will be small and I will be dancing. I will be dancing. I don’t like you. I don’t like you.”

For a moment Ali addresses the translator: “Tell him I don’t like him.”

Then back to Inoki: “You’re ugly. I will destroy you. Tomorrow. I want you tomorrow… Sayonara. Sayonara motherfu—”

Ali’s weight came in at 99 kilograms. A true American, Ali replied, “How much is that in English?”

Ali and Japanese culture

Despite how much Ali loved talking to the press, there isn’t much on the public record documenting his day-to-day experiences while in Japan. On one day, Gross writes, Ali went for a “five-mile morning jog in the Tokyo rain,” and on a different day he visited a “camera factory.”

Ali did sometimes embrace the Japanese public outside the professional ring, however. Ali’s brother, Rahaman Ali, did manage to describe in his new book, "My Brother, Muhammad Ali," just how much Ali enjoyed his time here: “Muhammad loved Japan,” he wrote. “He took pleasure in mixing with the common folk and revelled in the media attention. He would be in a limousine on his way to some promotional opportunity, and suddenly he’d begin to shout, ‘Hey, I see some people in the street! Let me out.’ Then he’d be gone, attracting people like flies. He got a big kick out of standing there for five minutes or so, until there were hundreds of people around him, chanting, ‘Ali! Ali! Ali!’ He couldn’t speak Japanese, of course, but his kindness and smile and the gentleness of his nature did all the talking he needed wherever he went. He travelled with an interpreter, but he would insist on connecting through gesture, and always managed to get his point across.”

On Sunday, June 20, over a thousand fans entered the Korakuen Hall, located next to the Tokyo Dome, three kilometers away from the Budokan. Korakuen Hall was built in 1962 specifically for martial arts events and this was a chance for fans to watch Ali and Inoki train up close. As Gross describes, Ali went through a few sessions of “shadow boxing” and “rope jumping,” while addressing the media. Sincerely, he hoped “Westernization” wouldn’t “destroy Japanese morals… I don’t want to see Japanese people lose their identity… Every country I go to I will tell people how wonderful Japan is.”

The fight

By the time the two men entered the ring, firm rules had been put in place.

There would be, as Inoki described later in an interview, “no tackling, no karate chops,” and “no punching on the mat.” Feeling “handicapped” by the rules (critics would also say he was scared of Ali’s right hook), Inoki chose to fight from the floor. As you can see from the highlights, most of the fight is Inoki moving on all fours, kicking Ali in the legs, as Ali danced around him, telling him to get up and fight and calling him a coward.

Stats for the fight tell the story. Ali threw a recorded seven punches in the fifteen rounds, landing four, one of them a vicious tenth round jab that Inoki felt, since Ali’s boxing gloves were lighter and there was less tape on his knuckles. As for Inoki’s kicks, they were devastating to Ali’s left leg. The official count has Inoki landing over 70 kicks (and one illegal elbow to the head after Ali was momentarily pulled to the floor). After the fight, Ali’s left leg had swelled to a point that hospitalization was required. Bruises, cuts and clotting—Ali was fortunate to not have suffered any long-term damage.

“I love Japan. I love the Japanese people. But there’s only one Japanese I don’t like, and that’s Inoki.” —Muhammad Ali, during a press conference for his 1976 fight with Antonio Inoki

The referee for the fight, the legendary “Judo” Gene Labell—perhaps the only man qualified at the time to officiate such a match, since he was skilled in both boxing and wrestling—was paid $5,000 in “crisp 100-dollar bills,” according to Gross. But even Labell was somewhat mystified by the cooked up rules of the fight. Inoki had at least three point violations, including a kick to the groin that almost caused Ali to leave the ring. By the end of the fight, the two judges were split, and Labell, the tiebreaker, chose to call it a draw. For fans and gamblers everywhere, anger set in.

As Jonathan Eig put it in his engrossing Ali biography, “A pillow fight would have offered more drama.”

Once the tie was announced, fans in the Budokan “rained trash” from the upper levels. They were furious and felt ripped off. Even more, they most likely felt that Ali and Inoki didn’t earn what had been advertised as a fight that offered $6.1 million in prize money. As Gross sharply describes, Ali had been guaranteed $3 million, but ended up only earning $1.8 million. Even that amount was problematic, since Ali’s manager at the time, Herbert Muhammad, reported that the 1.8 mil had been “split up” and suspicious activity on the part of a company called Top Rank, run by Bob Arum.

Ali and Inoki’s world peace friendship

Both fighters survived the embarrassment that came with this fight and became friends. A year later, in 1977, Inoki attended Ali’s marriage ceremony (to his third wife, Veronica Porsche). As Ali’s Parkinson’s worsened, Inoki’s wrestling career wrapped up, and he parlayed his popularity into a career in politics after being elected to the House of Councillors in 1989 and again in 2013 under the banner of his self-made “Sports Peace Party.”

Inoki—who lived for most of his childhood in Brazil—had a strong desire to use sports as a way to promote global peace, especially in hostile countries. In August 1990, as Saddam Hussein went into Kuwait, over 200 Japanese residents of Kuwait were held hostage in camps in Iraq, as well as hundreds of Americans. Inoki and Ali both had a hand in ushering the release of many of the hostages before the bombing started.

Again, in 1995, Inoki helped organize an event in Pyongyang, North Korea, asking Ali to join him (and also Ric Flair and other wrestlers) on a diplomatic peace mission. He did this partly to greaten his chances of being re-elected to the House of Councillors, but also as a way to start some sort of dialogue between Kim Jong-Il and the rest of the world.

The event was dubbed the “Collision in Korea,” as writer Mimi Hanaoka reported in her Grantland article, “Wrestler, Statesman, Hostage Negotiator, Legend: The Life of Antonio Inoki.” It was “a two-day show orchestrated by North Korea, Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling, and [Inoki’s company] New Japan Pro Wrestling.” As Hanaoka admits, the 380,000 who attended was probably inflated by North Korean officials and Kim Jong-Il, who’d only been in power for a year after his father’s death and desired to show a strong front.

Finally, in 1998, Inoki once again invited Ali to his final wrestling match at the Tokyo Dome. As Gross writes, Ali “sat ringside,” watching a friend he’d gained from a fight he no longer regretted. “In the ring, we were tough opponents,” he said diplomatically. “After that, we built love and friendship with mutual respect. So, I feel a little less lonely now that Antonio has retired… Inoki and I put our best efforts into making world peace through sports, to prove there is only one mankind beyond the sexual, ethnical, or cultural differences. It is my pleasure to come here today.”

Our next Japan Yesterday will feature Commodore Matthew Perry’s expedition to Japan in 1852.

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series:

Volume 2 (September 2019 – present)

- Eleanor Roosevelt visits ‘burakumin’ and Emperor Hirohito in 1953

- Charles and Anne Lindbergh fly 7,000 miles to Japan in 1931

- A young Douglas MacArthur visits Japan in 1905

- J. Robert Oppenheimer father of the atomic bomb visits post-war Japan

- Alexander Graham falls asleep meeting Emperor Meiji

- Frank Lloyd Wright designs Japan’s Imperial Hotel during a mid-life crisis

Volume 1 (November 2018 – May 2019)

- The ‘Sultan of Swat’ Babe Ruth visits Japan

- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

- Margaret Sanger brings 'dangerous thoughts' to Japan in 1922

- Bertrand Russell’s blinding Japanese resurrection

- Audrey Hepburn casts a spell over post-war Japan

- Ralph Ellison makes himself visible in 1950s Japan

- John Hersey visits the ruins of Hiroshima in 1946

- Russia’s Nicholas II is scarred for life in 1891 Japan

Patrick Parr is the author of One Week in America: The 1968 Notre Dame Literary Festival and a Changing Nation (March 2021). His previous book is The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age, now available in paperback.

© Japan Today

7 Comments

Login to comment

Jessie Lee

This was more of a show exhibition than a real fight, although it was a bit of a pioneer in raising consciousness of MMA movement

kohakuebisu

BigYen has called it a carnival, but I dunno, maybe a pantomime or a circus.

Ali was an entertainer and did a lot more than punch people in a ring, which he was very good at as a sportsman. If he was happy to do this, even if just for the money, then all's well I suppose.

lolozo79

.....to start some sort of dialogue between Kim Jong Un and the rest of the world.

In 1995 ? Kim Jong Un would've been a ten year old.

As for the Ali/Inoki bout, I remember watching footage of the match. One guy crawling around on the floor, the other spouting "Inoki coward!" every five minutes. Not exactly the most thrilling of matches would be an understatement.

Spitfire

Great article.

More like this please Japan Today.

Thank you.

Moderator

You can see the links to the series at the end of the article. There are more to come.

kyuudou

Excellent content. One nitpick, however about this:

According to Wikipedia, Inoki and his family didn't move to Brazil until he was 14, and he returned only 3 years later at the age of 17 to train with Rikidozan. Hmm. I think it would be more accurate to say that he spent most of his childhood in Japan and went abroad to Brazil as a teenager before returning home? "Most of his childhood" would be like if he left Japan before starting elementary school, in my opinion.

Also, if this match would've gone by Vale Tudo style no holds barred rules, Inoki would've immediately taken Ali down and submitted him in less than a minute. That's probably why the rules weren't made clear until the last minute since it was such a mismatch of styles and they wanted to make a good "show" of these two world superstars while not making a laughingstock of boxing which was at its peak in terms of popularity and financial prosperity at that time.

Would love to see a series of articles on judo master and Gracie Killer Masahiko Kimura who dabbled in the pro wrestling world that Inoki ran in. You guys could make a whole series of articles out of the Japanese origins of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu alone! I think it would be fascinating for any English-speaking Japanese culture buff who didn't already know about this stuff.