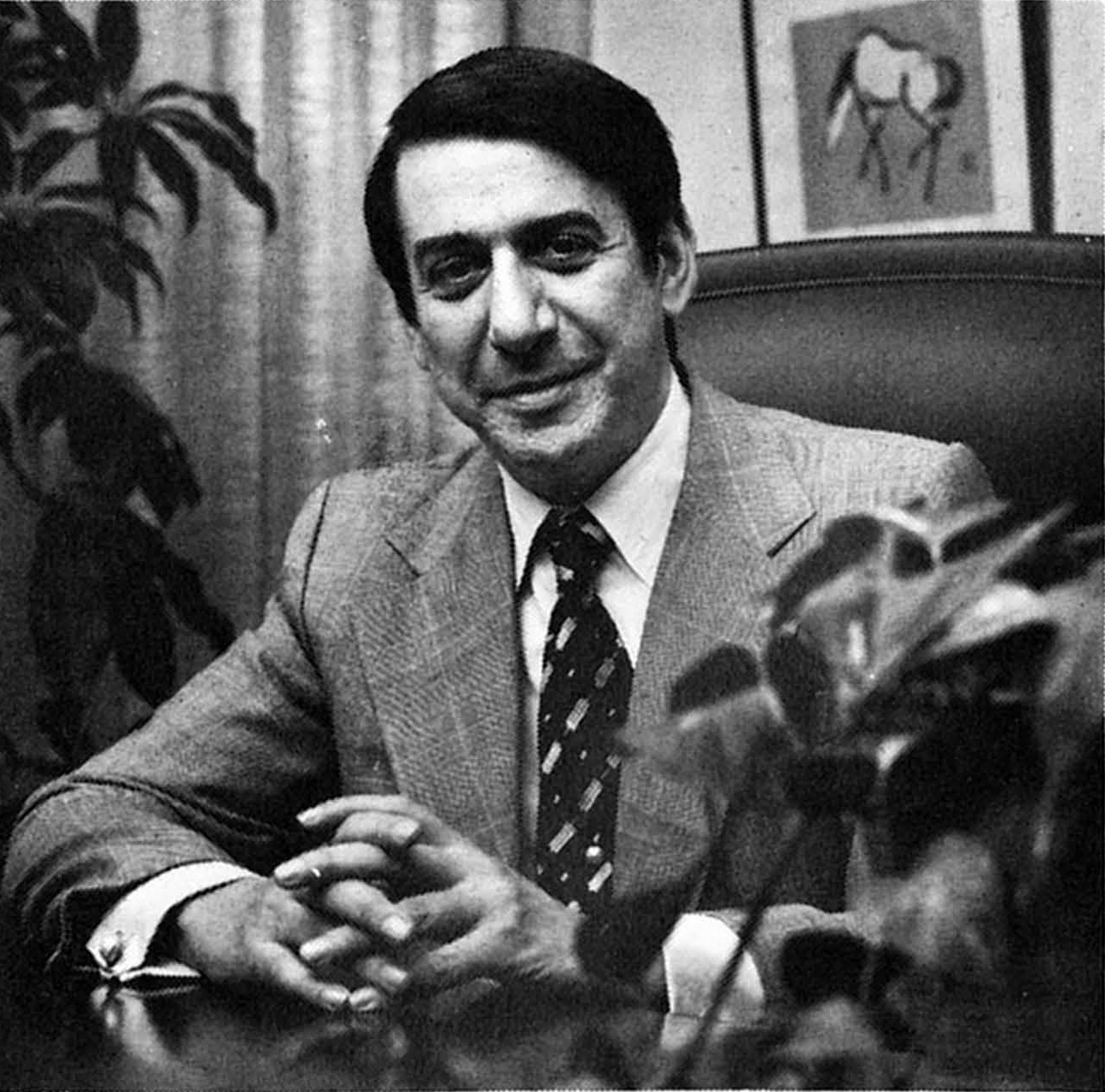

It was 1954. The Korean War’s armistice had been signed, and David M. Rosen, 24, a member of the United States Air Force, had returned to Japan, where he’d spent most of his time during the conflict. After a brief but unsuccessful attempt at starting an America-Japan photo art business from the U.S., Rosen moved to Tokyo looking to start fresh but remain in the photo world.

“At that point in time,” Rosen said in a rare 1996 interview for the video game magazine Next Generation, “the Japanese had a great need for ID photos. You needed an ID photo for school applications, for rice ration cards, for railway cards, and for employment. My idea was to adapt and import those little automated photo booths from the U.S. to Japan.”

For the next two years, Rosen dug in, learning all about the intricacies weaved into Japanese regulations. Import licenses back then were divided into three categories: “‘Absolute Necessities,’” explained Rosen, “‘Non-Necessity But Desirable,’ and ‘Luxury.’” So as Rosen muddled his way through licensing red tape with his Photorama booths, he began to witness the Japanese economy spike thanks in part to U.S. military spending during the Korean War.

“So around ’56 or ’57, I recognized that there was starting to be some disposable income.”

Rosen Enterprises

Overworked businessmen were finely giving themselves a break from what was then a six-and-a-half-day work week and spending their salary on games such as “Pachinko, dance studios, bars, and cabarets.” Rosen had no interest in these, however.

According to author Ken Horowitz’s book, The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games, Rosen still had fond memories of “penny arcade games” on Coney Island during his childhood years, playing spring-loaded, non-electric pinball machines. Coin-operated arcade games had yet to reach Japan’s mainstream culture, remaining only on military bases.

Rosen had no real tech background, but he was a savvy businessman, and he quickly identified an opening in the Japanese market. With the help of his wife, Masako, who he married in 1954, Rosen, as Horowitz explains, “transitioned to importing luxury items to Japan, later including coin-operated games, which were wildly successful.”

“We were stripping the cabinets off the old machines, just keeping the mechanisms and creating a new jungle environments from scratch.” —David Rosen

The word “luxury” in this quote is important, since it meant having to build a convincing case so that Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) would grant him a license. As Rosen recalled: “It took me over one year with a lot of effort — and certainly a lot of introductions — to convince MITI that coin-ops would be good for leisure. Finally, they granted me a license for $100,000, which meant I could purchase $100,000 worth of coin-ops, and bring them to Japan.”

The American coin-op game market was stagnant in these years, Chicago being its manufacturing epicenter. Rosen flew back to America and was able to find a stockpile of used coin-op machines in various warehouses. Rosen paid between $200 to $1,000 for these used games, but after two months of use in Japan, Rosen had made his money back. “The air gun games were in big supply and yet very popular in Japan,” explained Rosen. “We were stripping the cabinets off the old machines, just keeping the mechanisms and creating new jungle environments from scratch.”

At this stage, Rosen Enterprises started to solidify its presence, leaning on its past Photorama success to build its network: “…we worked out a very good relationship with various movie studios, primarily Toho and [Shochiku], so they made their locations available to us.”

Competition eventually came. “I probably had the civilian marketplace to myself for about two years,” said Rosen, “but then other companies learned how we were importing and under what classification.” Primarily, there were two main competitors, Taito (which at the time focused more on jukeboxes) and Nihon Goraku Bussan, the latter now more historically known as Service Games.

Service Games

I’ve started with Rosen, but the story of Sega truly starts in Hawaii, in 1945, with three partners ponying up $50,000 to start Service Games — game distributor Irving Bromberg, Martin Bromley (Irving’s son) and James Humpert. Like Rosen, the three men had been a part of the American military, and after the end of World War II, Service Games bought the Army’s slot and amusement machines and shipped them to military bases in Japan and around the world.

By February 1952, Service Games had expanded to military bases in Japan, but, as Horowitz wisely documents, the American government, in 1951, had passed the Transportation of Gambling Devices Act (or the Johnson Act). Suddenly, the slot machines Service Games had were illegal to ship anywhere the law prohibited gambling. The Johnson Act even banned such machines on military bases.

The loophole was to go international. For the rest of the 1950s, Service Games straddled the legal lines, maintaining a presence in Panama, South Korea, South Vietnam and the Philippines, selling both slot and amusement machines to American military bases around the world. While Rosen Enterprises developed deeper business roots in Japan, Service Games remained in fringe markets — global, but extremely limited from a partnership standpoint.

By the end of the decade, however, Service Games’s brand image took a hit. Horowitz writes that the company “was accused of everything from bribery to tax evasion and coercion.” By 1960, Service Games Japan had been “banned from U.S. bases in Japan and the Philippines,” eventually dissolving in May the same year.

Two Japanese companies swooped in to take over this vacated coin-op market share: Nihon Goraku Bussan Kabushiki Kaisha (Japanese Amusement Products Company, Inc.) and Nihon Kikai Seizo KK (Japanese Machine Manufacturers Co., Inc). By 1964, these two companies had merged.

So where does the name Sega come from?

Well, as early as April 1954, Service Games had been using the name “Sega” on its refurbished coin-op amusement and slot machines. Once Service Games dissolved, the name was carried over by the two Japanese companies, with Nihon Kikai Seizo capitalizing on the name’s already established brand awareness by filing trademark applications for “Sega” in 1962 according to game historian Keith Smith. In June 1964, Nihon Goraku Bussan chose to acquire Nihon Kikai Seizo, solidifying its place in the coin-op marketplace — and causing Rosen Enterprises to worry about its future.

The birth of Sega Enterprises

“[Nihon Goraku] was by far the larger company, and Sega was their brand name,” admitted Rosen. But Rosen Enterprises was not in trouble. Rather, in the mid-1960s, Rosen saw a stagnation across the entire coin-op game marketplace, believing (in Horowitz’s words) that “the games being released were far too alike.” Rosen believed “it was time for Sega to begin creating new games.”

In July 1965, Nihon Goraku Bussan acquired Rosen Enterprises, but the acquisition acted more like a merger. For starters, David Rosen was placed as CEO and managing director, his wife Masako also taking a director role. Rosen and others also agreed it was best to ax the manufacturing of slot machines from their bottom line, most likely to cut away from the illegal accusations leveled upon Service Games in the past. As a final touch, they combined names, officially becoming Sega Enterprises, Ltd.

With renewed company strength, Rosen pursued a way for Sega to create its own game. As video game historian Alexander Smith describes so clearly, around the time of the merger, Namco founder and inventor Masaya Nakamura had found success installing rooftop amusement parks for Matsuya and Mitsukoshi department stores — this may explain why in just about every department store in Japan the top floor is a game center — and had invented a three-player game called Periscope.

Years later, Rosen explained Periscope concisely: “It was a simple game. You stood at one end and shot at cutout ships running on a chain through a periscope… The aiming device looked like a real periscope and the player had to release torpedoes in time to hit the ships. It sounds simple today, but at the time it was somewhat revolutionary.”

Nakamura’s version was built for three participants to compete at the same time, but that made for a massive booth, which meant most department stores did not have enough room for it. Instead of giving up on the idea, Rosen adapted Nakamura’s game into a one-player unit. The cost went down, but Periscope was still far more expensive than other games of its kind. It took some coaxing, but Sega was able to convince operators to charge 25 cents for each go. This, Rosen admitted, “was a turning point for coin-ops,” and launched Sega into “the export business.”

For many Americans, a roll of quarters became a necessity before heading to the arcade. For that, you can thank Sega Enterprises.

Next up in the “When They Opened in Japan” series will be how Baskin-Robbins entered the Japanese market in 1974.

Other stories in "When They Opened in Japan":

- Ford’s Model T lands on Japanese soil in 1913

- Coca-Cola storms Japanese market in the 1950s

- Loy Weston brings Kentucky Fried Chicken to 1970s Japan

- Starbucks debuts in Ginza in 1996

Patrick Parr’s second book, One Week in America: The 1968 Notre Dame Literary Festival and a Changing Nation, was released in March 2021 and is available through Amazon, Kinokuniya and Kobo. His previous book The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age, is available in paperback.

© Japan Today

3 Comments

Login to comment

Jay

I remember playing 'Alex Kidd in Miracle World' - the free built-in game on the Sega Master System - and thinking: "This is the pinnacle of gaming. Video games cannot possibly get any better than this."

Turns out I was correct.

InsightfulCitizen

A great story.

餓死鬼

Give me the Cyber Razor Cut.