On April 18, 1953, Bob Krauss, writing for the Honolulu Advertiser, attended a Marian Anderson concert. Tickets had been sold out for weeks, and as Krauss listened to Anderson, a contralto, he couldn’t help but become spellbound as she sang. “What you notice first are her eyes. They’re like windows you can look through into the place her music comes from. They can sparkle and they can be coy but usually, to me anyway, they reflected an understanding of suffering…” For Krauss, it was Anderson’s “spirituals,” especially her hymn, “They Crucified My Lord,” which “moved me most of all.”

About a week later, Anderson left Honolulu and arrived in Tokyo on April 27. Her month-long visit was packed, culminating in a historic visit to the royal palace.

First impressions

By 1953, Marian Anderson had given over a thousand performances in her lifetime. The concert hall had become her second home. But what continued to change were the audiences she performed for. She could sense their engagement, and even if she was performing in Europe or the United States, she fed off the energy of the audience before her.

When performing in Japan, however, the audience’s energy was different, almost confounding: “The way the Japanese listened was extraordinary,” Anderson later recalled in her autobiography, And My Lord, What a Morning. “The concentration was intense and the quietness almost uncanny. No one seemed to stir, and at first I was conscious of the deep silence and immobility. They were not upsetting in any way, but they made me feel that a similar intensity was expected of me.”

While in Tokyo, Anderson stayed in a suite at the Imperial Hotel. The Japanese Broadcasting Corporation (NHK), which sponsored her trip, made sure to take care of any and all complications. Even in 1953, Anderson had experienced difficulties finding accommodations in segregated America, but in Japan, she was treated as royalty. “When we left Tokyo to appear in other cities we found ourselves traveling as a party of eight,” Anderson remembered. “A young woman was provided as an interpreter, and there were four men to serve us in other capacities. One young man was sent along to be banker and cashier; he carried the money and paid bills at hotels, restaurants, and shops.”

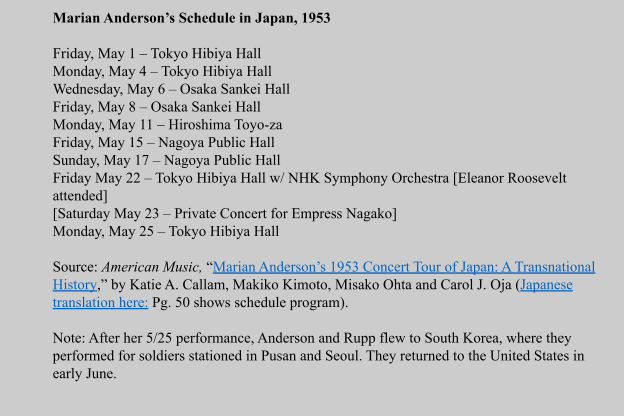

With everything taken care of, Anderson was able to focus on her performances, although the lack of flexibility in her schedule proved taxing at times. Anderson observed how the Japanese staff around her were “indefatigable planners,” and wrote that her “schedule was as rigid as a railroad timetable. Days were laid out in units of three — one for sightseeing, and this was planned down to the minute; one for a concert; and one, praise be, for rest.”

The NHK had requested that Anderson’s concerts be very similar to what she performed in the United States. Still, they did have some preferences, such as the work of Austrian composer Franz Schubert (1797-1828) and German composer Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). As for spirituals, the achingly powerful “Deep River,” was at the top of their list. The spiritual, written by an unknown African American in the 19th century, is one of Anderson’s greatest interpretations.

Her voice captures the pain and longing embedded in the song’s history:

The church

As author Raymond Arsenault described in his book, The Sound of Freedom, Anderson had started to love music as soon as she could walk. “Before she turned two,” Arsenault wrote, “she was already singing made-up songs while banging on a toy piano, and by the age of four everyone in the family recognized that she had a gift for singing.” Voice lessons were expensive, however, and Anderson’s parents struggled financially. Her father, John Anderson, a “devout Baptist,” worked in the Philadelphia area as a general laborer while her mother, Anna, a schoolteacher at heart, had no choice but to take on odd jobs, from “scrubbing floors” to “working in a tobacco factory,” doing what she could to raise her three daughters, Marian being the oldest.

It was when Marian joined her Baptist junior church choir at the age of 6 that her voice started to gain the public spotlight, and it was where she found a home in the alto section. “The music we had to sing was not very high, and I could just as well have sung the soprano part, but there were always more sopranos than altos, and I thought I would like to be where I was needed most.” But when she was 12 years old, Marian’s father died after a tragic accident at work. She would need to grow up quickly, her voice becoming a source of family income.

The empress

Anderson had come a long way from her modest upbringing. Now, at 56, she had famously performed in front of the Lincoln Memorial in 1939, and traveled the world. But it was her humility and her desire to keep the soul of a song of primary importance that brought her universal acclaim, and even the attention of Empress Nagako (Kojun), who invited the singer to the royal palace for a short performance.

“It is so true that no matter how big a nation is, it is no stronger than its weakest people. And as long as you keep a person down some part of you has to be down there to hold them down. So that means you cannot soar as you might otherwise.” —Marian Anderson

On May 23, 1953, Anderson arrived at the royal palace. In her autobiography, she remembered the visit vividly: “When we arrived at the palace we were taken to a reception room. We heard a car pulling into the drive, and Franz [Rupp; Marian’s accompanist] hurried over to the window, eager to see the Empress arriving, but he was told that one did not look out of windows when royal personages were appearing.”

Before their concert, the royal palace put on for Anderson and Rupp their own “special entertainment.” As Anderson recalled, “The court orchestra, of ancient instruments unfamiliar to us, played for us, producing strange and eerie sounds. The musicians wore fantastic costumes, and then in the garden on a platform some male dancers appeared, wearing even more fantastic costumes, and they did some unusual dances.” Apparently a program sheet offering explanations was not given to Anderson at the time.

After the context-less (but probably Noh) performance, it was Anderson’s time. She and Franz “were led into another room, which had rising tiers of seats. There was a stairway in the center of this arrangement, leading to the topmost seats. At the apex sat the Empress, and on either side of her was one of her children. Below her at her left sat the women of the court, and below her at her right the men.”

Anderson chose “four or five German songs” along with her magnificent rendition of “Ave Maria,” concluding with spirituals. For thirty minutes, the empress and other family (it’s uncertain where Hirohito was) were captivated by Anderson. Afterward, Nagako met with Anderson in a reception hall. Short pleasantries were exchanged — how has your tour been, what do you think of Japan — and Nagako then gave Anderson “a hand-carved figure of a No[h] performer” and an elegant “lacquer box” for Franz. The royal palace then made sure to wrap the gifts in “lovely boxes” and placed them near the exit.

For Marian, the ceremonial formalities shown to her in Japan impressed her the most. “Though it has become Western in many ways, the essence of an old tradition remains,” she’d later state.

Back in the United States, newspaper columnists viewed Anderson’s performance through a racially-minded lens, declaring to their readers that Anderson was the first person of African descent to ever set foot in the royal palace. The Associated Press, for example, wrote that “Japan’s Imperial Court today had a Negro guest for the first time in its 2,600-year history.” While this is more or less true, it would not have mattered too much to Anderson, who didn’t feel the need to mention this piece of history in her autobiography. She wanted her art to speak for itself.

As biographer Allan Keiler documented in his biography, Marian Anderson: A Singer’s Journey, between April 27 and May 26, Anderson gave a total of 10 concerts in Japan, four in Tokyo, and several more in Nagoya, Osaka and Hiroshima. For most of her career, Anderson made sure to abstain from giving her opinion on social matters. In Nagoya, she was asked a potentially thorny question regarding “what changes,” as Keiler reported, “she thought Japanese women should adopt.” Anderson chose to abstain, telling the questioner that “since I did not know [Japanese women] personally I could not intelligently suggest changes.”

Anderson’s desire to step away from controversy earned criticism from several media outlets, who believed the globally-known singer should use her platform to push for change. But Anderson was far more interested in commanding the minds of an audience in a concert hall than commanding a group of demonstrators on the streets. With every country she visited, Anderson’s symbolic impact had its own power, and her stage success helped to usher in a new generation of classically-trained African American singers, such as Leontyne Price.

That said, it’s worth noting that Anderson did indeed support the civil rights movement, especially once the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1957) had changed the national conversation and attracted worldwide attention. While touring India in 1957, Anderson accepted an interview request by the All India Radio station. During the revealing interview in New Delhi, Anderson talked with Tara Ali Baig, a respected Indian author and social reformer. In a roundabout way, Baig brought up the matter of racial prejudice, and Anderson was prepared with this gem of a sentence: “It is so true that no matter how big a nation is, it is no stronger than its weakest people. And as long as you keep a person down some part of you has to be down there to hold them down. So that means you cannot soar as you might otherwise.”

At the end of her trip, on May 22, Marian Anderson briefly reconnected with Eleanor Roosevelt, the former first lady who was about to embark on her own scheduled trip across Japan, and who helped to organize Anderson’s historic 1939 Lincoln Memorial concert. They embraced, and Roosevelt made sure to take note of the meeting in her popular My Day column: “She sings here tonight and we are going to hear her, which for me is a great pleasure.”

Our next Japan Yesterday will feature scholar William Elliot Griffis and his time teaching in Japan in 1871.

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series:

Volume 2 (September 2019 – present)

- Robert Kennedy confronts communist hecklers at Waseda University in 1962

- Commodore Perry’s black ships deliver a letter to Japan in July 1853

- The story of Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s trip to Shuri Castle in 1853

- Japanese journalist witnessed the death of Malcolm X

- Muhammad Ali fights Antonio Inoki at the Nippon Budokan in 1976

- Eleanor Roosevelt visits ‘burakumin’ and Emperor Hirohito in 1953

- Charles and Anne Lindbergh fly 7,000 miles to Japan in 1931

- A young Douglas MacArthur visits Japan in 1905

- J. Robert Oppenheimer father of the atomic bomb visits post-war Japan

- Alexander Graham Bell falls asleep meeting Emperor Meiji

- Frank Lloyd Wright designs Japan’s Imperial Hotel during a midlife crisis

Volume 1 (November 2018 – May 2019)

- The ‘Sultan of Swat’ Babe Ruth visits Japan

- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

- Margaret Sanger brings 'dangerous thoughts' to Japan in 1922

- Bertrand Russell’s blinding Japanese resurrection

- Audrey Hepburn casts a spell over post-war Japan

- Ralph Ellison makes himself visible in 1950s Japan

- John Hersey visits the ruins of Hiroshima in 1946

- Russia’s Nicholas II is scarred for life in 1891 Japan

Patrick Parr’s second book, One Week in America: The 1968 Notre Dame Literary Festival and a Changing Nation, was released on March 2, and is available through Kinokuniya and Kobo. His previous book is The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age, now available in paperback.

© Japan Today

9 Comments

Login to comment

asiafriend

What a difference from today when back then the black family was a close unit and single parent mothers were only in the 24 % range. Today, 74 %. Anyone wonder why the black community has so many problems, such as crime because there is no father figure? And yet, BLM wants to eliminate the nuclear family.

asiafriend

If a black person becomes mayor of a town, for example, the liberal press always says that it is a first for blacks, stroking the sense of segregation. Why not just call the person a mayor and show the respect due? Do we ever hear of the first Hungarian-American mayor? Of course not.

kokoro7

Glad she rose above the racial fray to focus on and exhibit her art. Anyone who tries to inject racism into it is incapable of understanding art and freedom.

Laguna

I absolutely love this series and look forward to each new installment.

Anonymous

”... newspaper columnists viewed ... through a racially-minded lens, ... [Anderson] was the first person of African descent to ever ....”.

It sounds like the same racially-minded lens is still used today - even more so.

BTW, the great Paul Robeson was her contemporary.

robert maes

It is not true that a nation is as weak as its weakest people. In that case the Uk would have lost the war, Belgium would stil be under Dutch rule and in Hongkong today everybody would speak Mandarin.

A nation is as strong as it’s ethics and morals and it’s strength and courage to defend them. A nation is as strong as the freedoms it allows to its citizens and the will of those citizens to defend those.

Harry_Gatto

How true.

dbsaiya

Thank you for this article and the video clips.