In 1864, 30-year-old Norwegian-American William Copeland (1834-1902) arrived in Yokohama. Copeland — described by Waseda professor Katsumata Senkichiro as a “tall and very imposing man” with “an attractive character” but “a bad drunk” — was starting over, again.

At birth, Copeland was given the name Johan Bartinius (later Martinius) Thoresen and spent his early years in Arendal, Norway before moving with his family 40 kilometers south along the coastline, to Lillesand, a village port. At an early age, brewing beer fascinated him and by the time he reached his teenage years he’d started learning the trade from a German brewmaster who lived in Norway. He’d spend five years learning the specifics of brewing, such as malting, wort production and fermentation.

By the early 1850s, Thoresen, the oldest of six other siblings, had grown restless, and sought to leave his home country. Two other siblings had become ship captains, so dreams of travel were common among the household. At some point, Thoresen decided to move to America, and like many European immigrants around this time, he decided to fundamentally change his identity. He became William Copeland.

Copeland’s time in America is shrouded in shadow. It is known that he became an American citizen, but in 1864, less than a year after the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War, Copeland headed west, eventually boarding a steamship that traveled across the Pacific. He eventually settled in the Yokohama district of Yamate.

From one civil war to another

Ever since the signing of the 1858 U.S.-Japan Treaty of Amity and Commerce, Japan had placed itself in a most uncomfortable predicament. Their traditional ways were being ushered out by the West, and samurai rebellions were frequent across the country around this time. For Copeland, there wasn’t much choice where to settle. He wasn’t an educator, like Lafcadio Hearn or William Elliot Griffis, so he couldn’t accept a teaching job in a rural area. Copeland was a businessman looking to make his mark.

Business historian Jeffrey W. Alexander, in his groundbreaking book, Brewed in Japan: The Evolution of the Japanese Beer Industry, does a wonderful job of not only digging into Copeland’s years in Japan but also placing into proper perspective the beer industry just before and after the Meiji Restoration. According to Alexander, after the 1858 Treaty, “arrivals from Europe and America soon settled in Yokohama, in a segregated district between the seashore and Yamate Hill, where they built numbered apartment flats, merchant offices, and small unregulated businesses.” Copeland was one of them.

Horses, dairy and then beer

Copeland didn’t immediately begin brewing. According to the Japan Weekly Mail, Yokohama’s English language newspaper at the time, Copeland “first started the drayage [horse-drawn carriage] business. He was also the first foreigner to engage in the dairy business and in beer brewing.”

Copeland wanted to utilize the brewing skills he’d learned back in Norway. He, like many, had grown tired of relying on imported bottles of Bass and various German brands that had traveled halfway across the world and lost most of its freshness.

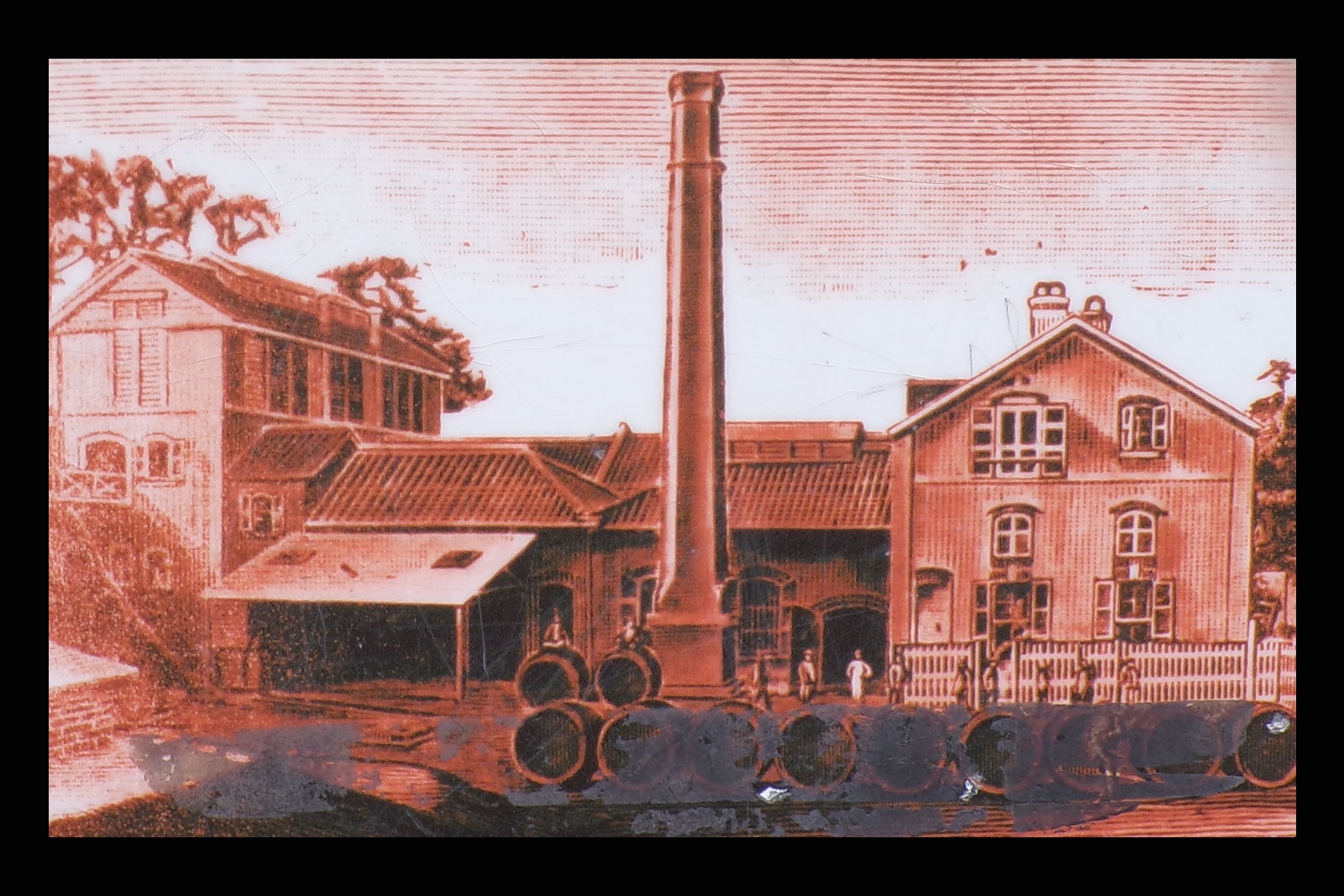

As Alexander documents, Copeland’s address was “No. 123 Bluff, Yokohama,” and in late 1869 through early 1870, he began setting up the first beer brewery in Japan. As noted by writer Tomoko Kamishima, Copeland’s determination to bring "real beer" to Japan was strong enough that he “dug a 210-meter cave into the side of a hill and used its low fixed temperature to help the beer mature.” For water, he chose Amanuma pond in Yamate (often simply called the “Bluff”) near his residence.

Within the heavily protected Yamate district was an area known as Kiyoizumi — izumi meaning "spring." Most likely drawing inspiration from his location, Copeland founded the Spring Valley Brewery in early 1870, serving three different kinds of beer: a classic wheat-centric “Bavarian Beer,” a heavily malty “Bavarian Bock Beer” with a goat logo inspired by the cat on the then-imported Guinness Stout, and a lighter, crisper “Lager Beer.” Copeland also shipped his unfiltered, unpasteurized beer via cask to local establishments.

I mention heavily protected because, in those early years, Copeland’s main customer base were British and French soldiers stationed around the Bluff to protect the segregated community from Japanese radicals angered by their presence in their country. As reported by Burke Wallis, once a resident of Yokohama, the soldiers remained until at least 1875, Copeland’s brewery a short walk away from their bases.

According to Alexander’s research, it may have been the British who drank Copeland’s beer the most. Called “Amanuma biyazake [beer sake]” at that time, Alexander quotes from the 11-volume history of Yokohama City put together by authors Kayama Michinosuke and Hotta Shozo, published between 1931-1933. This massive source shows proof of how Copeland’s creation was appreciated.

“Indeed, Amanuma biyazake is certainly one thing that the British officers and men stationed at the nearby Teppoba training grounds [a rifle range…], as well as the foreign residents of Yokohama, count as indispensable.”

A bumpy 15-year run

Copeland soon went into business with a German-American brewer named Emil Wiegand, who, like Copeland, had immigrated to America and become a citizen, eventually moving to Japan in 1868. Wiegand, according to some outstanding detective work by beer blogger Martyn Cornell, first worked in Dutch merchant MJB Noordhoek Hegt’s Brewery, which rivaled Copeland’s Spring Valley until 1876, when the breweries agreed to merge. Hegt allowed Copeland and Wiegand to carry on their business under the SVB name.

Copeland and Wiegand clashed. By the end of 1879, Wiegand, reports Cornell, accused Copeland of “fraudulent acts and other irregularities,” suing him in order to break their partnership and receive his profit share of the brewery. Since the Spring Valley Brewery was not under the jurisdiction of Japanese law, due to the 1858 treaty (and didn’t have to pay local taxes) the American Consul General stepped in to review the case, ruling in favor of Copeland. Wiegand left Japan, passing away in San Francisco in 1887.

Legal trouble struck Copeland again in 1880, when his head clerk, named Eyton, filed a lawsuit against the brewery. Already struggling with funds after losing then buying back his brewery during the Wiegand case, Eyton’s lawsuit caused Copeland to declare bankruptcy. As Alexander reports in Brewed in Japan, Spring Valley “was unable to weather the recession and deflation of 1882.”

Copeland’s brewery remained on financial life support until early 1885, when the Japan Brewing Company — a precursor to Kirin Brewery — swooped in and found a way to circumvent business laws that dissuaded Japanese entrepreneurs from purchasing Western-owned companies on Japanese soil (and vice versa). The Japan Brewing Company took over Copeland’s Spring Valley site and ran the brewery for 22 years, eventually becoming Kirin in 1907.

As for our main character, Mr. Copeland, he was proud of how long he was able to endure in Yamate.

“I experienced 15 years of success in this country as a brewer of Anglo-German beer,” he wrote during his bankruptcy court ruling.

Sailors and prostitution

From 1886 to his death in February 1902, Copeland and his wife Umeko Katsumata did their best to stay afloat. According to Alexander, “In 1886, he moved next door to building No. 212, remodeled his house into a beer garden, and began selling beer next to his old factory.”

Copeland’s now very personal venture had a clientele mainly of sailors, many of whom broke Copeland’s “thick glass mugs,” causing the brewer to switch to “galvanized metal mugs.”

Intermittent stints in Hawaii and Guatemala followed. As the years passed, more and more Westerners came to Yamate, causing societal consternation, and by July 1893, the area around Copeland’s brewery had become flooded with illegal activities, including prostitution.

Copeland’s “drinking saloon,” as a correspondent for Vancouver’s Daily News-Advertiser reported, had become a place where “Japanese women and foreign sailors met for the purposes of prostitution.” The correspondent went on to accuse Yokohama’s port to be “disgraceful,” and Chinatown “full of the vilest grog shops,” yet “the Japanese police have long been powerless to stop them.”

Yokohama’s Japan Weekly Mail in August 1893 quotes a “contemporary” criticizing Yamate at the time. “The regulations for the government of the foreign concession are so loose that immorality and gambling are rampant, as if the people were living in a state of savagery.”

It’s unclear how accountable Copeland was. This very public case was not reported in Alexander’s book nor any other sources used for this article, but it’s clear that his case was being used to show that, yes: Japanese law enforcement could hold some individuals in Yamate accountable.

Here is the Consul General’s decision on the matter, printed in Vancouver’s Advertiser:

“It has been made very clear to the Court that William Copeland, the defendant and accused, is the owner of the property lot No. 122 on the Bluff Foreign Settlement, and it is also clearly proven that prostitution has been going on there habitually and for some time prior to June 1st, 1893. While it is not so clear that the accused was the active cause of those illegal and immoral acts, yet there is sufficient evidence to show that he was in a position to know, and in a position to prevent such acts, and must to a certain extent have been cognizant of them. In any event under the law a husband cannot screen or excuse himself behind his wife in such a case as this. Therefore the Court finds him guilty as charged in the complaint, and sentences him to pay a fine of $25 and the costs of the proceedings herein, and he stands committed to prison till such fine be paid unless he is discharged from prison by further order of the court.”

A tarnished and restored legacy

The result of the prostitution case was reported in local newspapers as far as New York, and most likely soured Copeland on remaining in Japan.

He ran a Japan-themed business in Guatemala for some time, and expressed to Umeko that he did not want to return to Japan, but in October 1901, stricken with heart disease, he did, only to pass away several months later, on Feb. 11.

The Japan Brewery had prospered, and had already begun selling a beer labeled “Kirin.”

As reported in Alexander’s book, their company chairman expressed the following during a meeting one day after Copeland’s death: “A few weeks ago, Copeland-kun and his wife [Umeko], who are poor and dying, returned from [Guatemala]. He is the originator of Spring Valley Brewery, the firm that fostered our firm, The Japan Brewery, so I think it is only just that our company should hold out a helping hand…However, Copeland died suddenly last night. Therefore, I think I’d like the company to cover the funeral expenses and give a gift to his widow as a humble token.”

They did and Umeko, who passed away in 1908, received aid from the company.

Copeland was given a respectful obituary on Feb. 15, 1902 in the Japan Weekly Mail, crediting his efforts to start the Spring Valley Brewery even though “the Japanese had not acquired the taste for beer and the venture was not attended with much success.”

Still, Kirin was thankful. Copeland had provided the foundation for their company.

Kirin has placed a monument memorializing the actual location of Copeland’s Spring Valley Brewery. It can be found here (Google Map), in Kirin Park, along Biyazake Street (another nod to Copeland’s Amanuma “beer sake”). And, as of 2024, if you walk into just about any convenience store, you’ll find Kirin’s craft beer imprint, Spring Valley, honoring Copeland’s pioneering brewery.

Next up in the “When They Opened in Japan” series is how Edmund Morel helped launch Japan’s railway system in 1870.

Other stories in "When They Opened in Japan":

- Baskin-Robbins brings 31 Flavors to Japan in 1974

- David Rosen helps launch Sega in Japan

- Ford’s Model T lands on Japanese soil in 1913

- Coca-Cola storms Japanese market in the 1950s

- Loy Weston brings Kentucky Fried Chicken to 1970s Japan

- Starbucks debuts in Ginza in 1996

Patrick Parr is professor of writing at Lakeland University Japan. His third book, Malcolm Before X, published by the University of Massachusetts Press, is now available for pre-order. His previous book, One Week in America: The 1968 Notre Dame Literary Festival and a Changing Nation is available through Amazon, Kinokuniya and Kobo.

© Japan Today

9 Comments

Login to comment

TheReprobate

An outstanding read! Thank you for publishing this series.

BertieWooster

Very interesting. A most enjoyable read.

MichaelBukakis

Well done

Cfields

Kirin beer is a great choice. Thank you for the interesting history. Both are very enjoyable.

jinjapan

I was always under the impression that Sapporo was the 1st brewery in Japan, but with these dates it would mean for sure that Copeland & Kirin were the 1st.

finally rich

I'm really enjoying the "When They Opened in Japan" series.

I suspect most japanese have no idea of the origins of most of the modern things surrounding them, from the endless memorable jingles everywhere to 'Sega', 'Kirin Beer' and the countless restaurant chains they believe its japanese. All gifts from the West.

The list is big enough to exclude all things and ideas their own people brought from the West: Suntory Whisky, all sorts of tech, etc.

timeon

Great story! Recently Spring Valley popped up everywhere, a bit more expensive but very nice, I love especially the silk ale one. I didn't know the story behind the name

Gene Hennigh

The beer in Japan is pretty darn good. I prefer Asahi but never turned my nose up at Kirin.

Alan Fujimoto

Thank you for the great story. When I was growing up in Yokohama in the 60s and 70s I lived 5 houses down the street from the park known to us as Kirin Koen. I revisited my old haunts in 2016 and I do have photos of the monument, but there seems to be no way to post them here.