Once upon a time, Ford was the top-selling automobile in Japan. In fact, from 1925 to 1936, as scholar J. Scott Mathews writes for the Michigan Historical Review, Henry Ford’s Model T “dominated automobile sales in Japan,” with Chevrolet a very close second. When Ford officially opened their plant in Yokohama’s Tsurumi ward in late 1924, Toyota, according to Mathews, “made power looms” while Nissan “did not exist, and Honda Soichiro was still a student.”

Ford’s relationship with Japan started as early as 1913, with “import-export companies,” but sales were minimal. Their main partner, Sale & Frazer, offered little in the way of advertising.

The American government had already deemed Japan’s infrastructure “ill-suited for automobiles.” On Sept. 1, 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake decimated roads and factories, but this did not deter Henry Ford from allowing then-head of exports Russell I. Roberge to visit multiple Asian countries, including Japan. Roberge saw potential for growth, despite the devastation, and started the rental process for a “waterfront property at No. 4 Midori-cho, Naka-ku, Yokohama, from the Yokohama Dock Company.” The plant was constructed to accommodate the assembly of Ford’s standard black Model T.

It was a questionable decision by Henry Ford, who for the last few years had been holding firm to his original vision of the Model T despite a rapid decline in sales due to a crowded marketplace offering an ever-increasing variety of cars. Mathews reminds readers of a famous line uttered by Ford when asked to consider producing his Model T in different colors. “You can have them any color you want boys, as long as they’re black.”

Welcome to Japan

In February 1925, Ford Japan was born, and Argentinian Benjamin Kopf, an up-and-coming manager who’d run Ford’s operation in Chile, was chosen to push Ford into the Japanese market.

Kopf, married with two children, was ambitious, but as Mathews rightfully notes, he may have felt in over his head after landing in Japan. Apparently, the new head of Ford Japan, writes Mathews, “knew nothing of Japan or its language…”

Woefully underprepared, Kopf “arrived with one shipment of knock-down (KD) Model Ts and the US Department of Commerce’s report on prospects for the automobile industry in hand.” That’s pretty much it.

But, Mathews continues, Kopf had “Ford’s name” — and extremely friendly business conditions.

Sale & Frazer’s efforts, while limited, helped pepper the Ford name in and around the Kanto area. The Japanese consumer public had at least heard of Ford.

As of February 1925, there was little to no automobile competition. Chevrolet was still two years away from registering annual sales in Japan.

Ford also had the ever-friendly Taisho Era (1912 - 1926) policies when it came to western companies. And, as Mathews reports, Japanese newspapers had begun to welcome advertising squares to help with their own bottom line.

In 1925, Ford sold nearly 3,450 Model T’s in Japan, the number more than doubling in 1926 due in large part to a full calendar year of sales and a more established market presence.

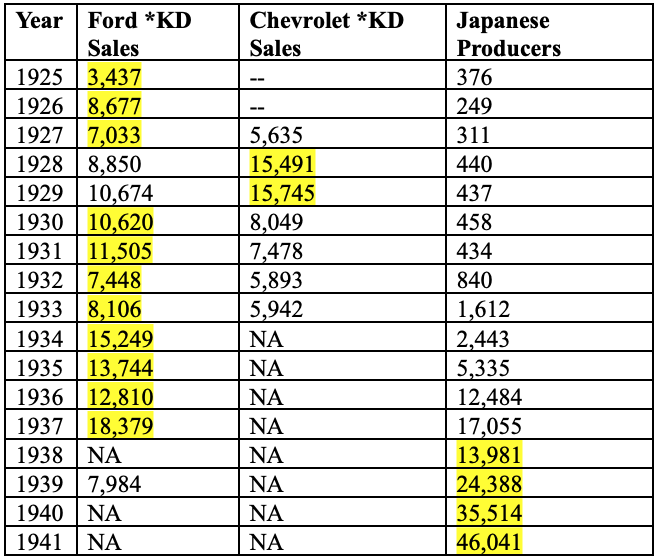

The following sales graph, reproduced here from Mathews’s article, shows a fascinating rise and fall of sales coinciding with Japan’s transition to a militaristically-minded government.

Automotive sales in Japan (1925–1941)

In 1927, Chevrolet/GM opened a plant in Osaka and sold trucks and sedans, its versatile offerings quickly overtaking Ford’s basic Model T vehicle. Ford was also, in 1927, reconstructing all its American plants to accommodate the manufacturing of its new Model A, a painful six-month process that meant laying off thousands of factory workers, and, as Henry Ford biographer Steven Watts writes in The People’s Tycoon, may have been “the biggest replacements of plant in the history of American industry.”

“…the only way for us to retain this important market is to take timely steps to manufacture locally before we are shut out of the market.” – Benjamin Kopf, Ford Japan

In Japan, as they waited for the Model A, Kopf continued to battle Chevrolet’s newer offerings, tipping the balance back to Ford by allowing for more flexible payment plans, since Ford had for the first few years demanded payment in full from the customer.

From 1930 through 1933, Ford and Chevrolet battled, Ford having a stronger, more traditional brand image and a reliable product, while Chevrolet had different models and designs to choose from. But in the middle of this competition, in September 1931, came the Mukden Incident, and the beginning of Japan’s invasion of Manchuria.

Helping a growing war machine

Both Ford and Chevrolet sold automobiles to the Japanese military during these years, though figures after 1933 are difficult to find.

According to scholar Masaru Udagawa’s research, Chevrolet had its third-most profitable year in 1934, bringing in nearly ¥2.7 million. GM (of which Chevrolet had joined in 1918) also, as Udagawa points out, had a policy of positioning its operation as “a local institution in each country…rather than a foreign concern doing business in that country.”

If Japan’s military ordered trucks, cars and sedans to help their soldiers fighting in Manchuria, both Chevrolet and Ford fulfilled those orders, choosing to ignore their government’s disapproval of the war.

But Ford stayed around longer than Chevrolet, who eventually left Japan in 1936 after failed “negotiations” with Nissan. I put quotes around negotiations because, as Udagawa suggests, Nissan had been attempting to slowly swallow up Chevrolet’s place in the market, one year at a time. As Japan’s military grew stronger, a nationalized automobile industry was inevitable.

Kopf saw this, and in a report dated 1935, he wrote that “when [Japan] seriously felt that it might become embroiled in warfare with one or more of the largest Western powers…desperate attempts [were] made to bring forth a complete, self-sufficient motor industry, almost regardless of cost; but it is intended that this industry shall be in the hands of the Japanese exclusively.” To Kopf, “…the only way for us to retain this important market is to take timely steps to manufacture locally before we are shut out of the market.”

Ford Japan had already been attempting to become more of an established presence. In April 1934, Ford attempted to purchase around 80 acres of land in Yokohama to build a production facility, but was denied by the Army, who believed that assisting “a foreign country at this time is to sabotage domestic manufacturing of automobiles indispensable in war. Japan will then have no auto industry of its own.”

Kopf and Ford Japan persisted, finally securing 90 acres of land. As Udagawa reports, even though the Army was not happy with the sale, city officials wrote that “Ford will build factories and provide technology. Even if a war breaks out, they cannot take the factories back to America.”

[More photos of the Nippon Ford Assembly Plant, Yokohama, c. 1930. via Old Tokyo.]

The exit

In the hours after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Benjamin Kopf ran to the Ford factory in Yokohama. He was on a mission, Mathews recounts, to “destroy some documents and to collect essential financial records to take to the US consulate for safekeeping.”

He managed to do so, but soon after learned “that some of his staff had been arrested.” Just as U.S. authorities arrested Japanese-Americans in Los Angeles and other places, Japan had started to round up Americans. Kopf, according to Mathews, “was able to leave Japan within a year, as were most Ford Japan employees who were not US citizens.”

Incredibly, throughout the war, Ford’s Yokohama plant was not damaged. In fact, during the Occupation years (1945–1952), the plant was used as “a barracks” for American soldiers. Ford was never able to return to its halcyon years of the 1920s, settling back into exporting cars to Japan starting in the 1970s. However, even this was less than profitable, and in 2016, after only selling around 5,000 cars and trucks in Japan, Ford decided to leave the country for good.

Next in the “When They Opened in Japan” series will be Sega Corporation’s complicated history with Japan, starting in 1940.

Other stories from "When They Opened in Japan":

- Coca-Cola storms Japanese market in the 1950s

- Loy Weston brings Kentucky Fried Chicken to 1970s Japan

- Starbucks debuts in Ginza in 1996

Patrick Parr’s second book, One Week in America: The 1968 Notre Dame Literary Festival and a Changing Nation, was released in March 2021 and is available through Amazon, Kinokuniya and Kobo. His previous book is The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age, now available in paperback. He teaches at Lakeland University Japan’s campus in Ryogoku.

© Japan Today

4 Comments

Login to comment

Jay

Forget Elon Musk, this is the brainchild of the man who REALLY revolutionized the car industry.

Henry Ford. A man as healthy and vibrant as Detroit itself (lol)

Back in the day, they used to say the Model T was like a bathtub - you knew you needed one but really didn't want to be seen in it.

And yes, even though you'd get to your destination quicker on foot, the Model T was, and is, an automotive legend.

factchecker

Once upon a time, Ford was the top-selling automobile in Japan.

TokyoLiving

He could have done a lot for the auto industry but his anti-Semitism and awarding of the "Grand Cross of the German Eagle" by Hitler is not forgotten..

TaiwanIsNotChina

Consider that Japan's population pre-war was 70 million and those numbers add up to maybe a couple hundred thousand. Yeah.