For those who love to be in nature or off the beaten path, but also want to feel that they are most definitely in Japan, Mt Hiko (aka Hikosan) in the mountains of eastern Fukuoka Prefecture may be just the ticket. The lush mountainsides are home to a number of hiking trails, many developed as part of the ascetic religious practices that have been observed here for centuries. At the same time, the once substantial religious community here has, through the exigencies of time, dwindled to give the area a “lost city” atmosphere that equally inspires the imagination.

In ancient times, the 1,200 meter peak of Hikosan and its two subordinate peaks were regarded as manifestations of three of Shinto’s deities: Izanami and Izanagi (the couple who fished the Japanese islands out of the sea) and their grandson, the progenitor of Japan’s imperial line.

During the introduction of Buddhism to Japan, native kami deities were syncretized to Buddhist deities, resulting in gongen (merged) deities. As a result, the three peaks of Hikosan eventually came to be regarded as Senju Kannon (the thousand-armed goddess of mercy), Shaka Nyorai (the Buddha of the present) and Amida Nyorai (the Buddha of the past).

Hikosan’s significance as a site for religious observation prospered with the development of shugendo, the syncretic mountain asceticism that developed in the seventh century as a particular blend of traditional Japanese folk practices with Buddhist rituals.

For 12 centuries Hikosan was home to a few thousand yamabushi (mountain ascetics) at any given time, all of them attracted to the isolation and inspiring landscape. Indeed, Hikosan was once regarded as one of the three major sacred sites for shugendo.

At one time, there were as many as 800 shukubo (monastic inns) operating on the mountainside to house pilgrims from around the country.

The remains of many of these shukubo can still be seen along the massive lantern-lined stone staircase leading up the mountainside to Hikosan Jingu and the central shrine complex. Shoyobo, a 180-year-old temple, and Kenyobo, with its pretty garden reminiscent of temple gardens two centuries ago, are two shukubo that still offer bohaku overnight stays, often paired with shugendo experiences.

During the four centuries leading up to the Edo Period (1603-1867), many samurai warriors and feudal lords supported the yamabushi and often themselves retreated to Hikosan for their own shugendo worship. Unfortunately, their presence occasionally also turned the mountainside into a battlefield. During the sixteenth century, nearly all of the wooden structures of the area were deliberately destroyed by fire, multiple times, including once by the great warrior Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Perhaps most devastating to Hikosan as a religious community, however, was the 1868 law separating Shintoism and Buddhism. The purpose of this law was to give precedence to Shinto as a state religion as part of the restoration of imperial power, since the emperor was said to be descended from Amaterasu, the primary deity of Shintoism. Needless to say, the movement meant a diminution of Buddhism, with many Buddhist temples forced to close or even destroyed. At Hikosan, the primary Buddhist temple was converted to a Shinto shrine, and remains so to this day, although it still looks like a temple in spite of its vermillion color. The three peaks also reverted to their earlier kami associations.

Many of the yamabushi became Shinto priests, or left the mountainside altogether. Among those who remained, a number became “hidden Buddhists”, continuing their shugendo practices in secret not unlike the “hidden Christians” who had been driven underground by religious persecution three centuries earlier.

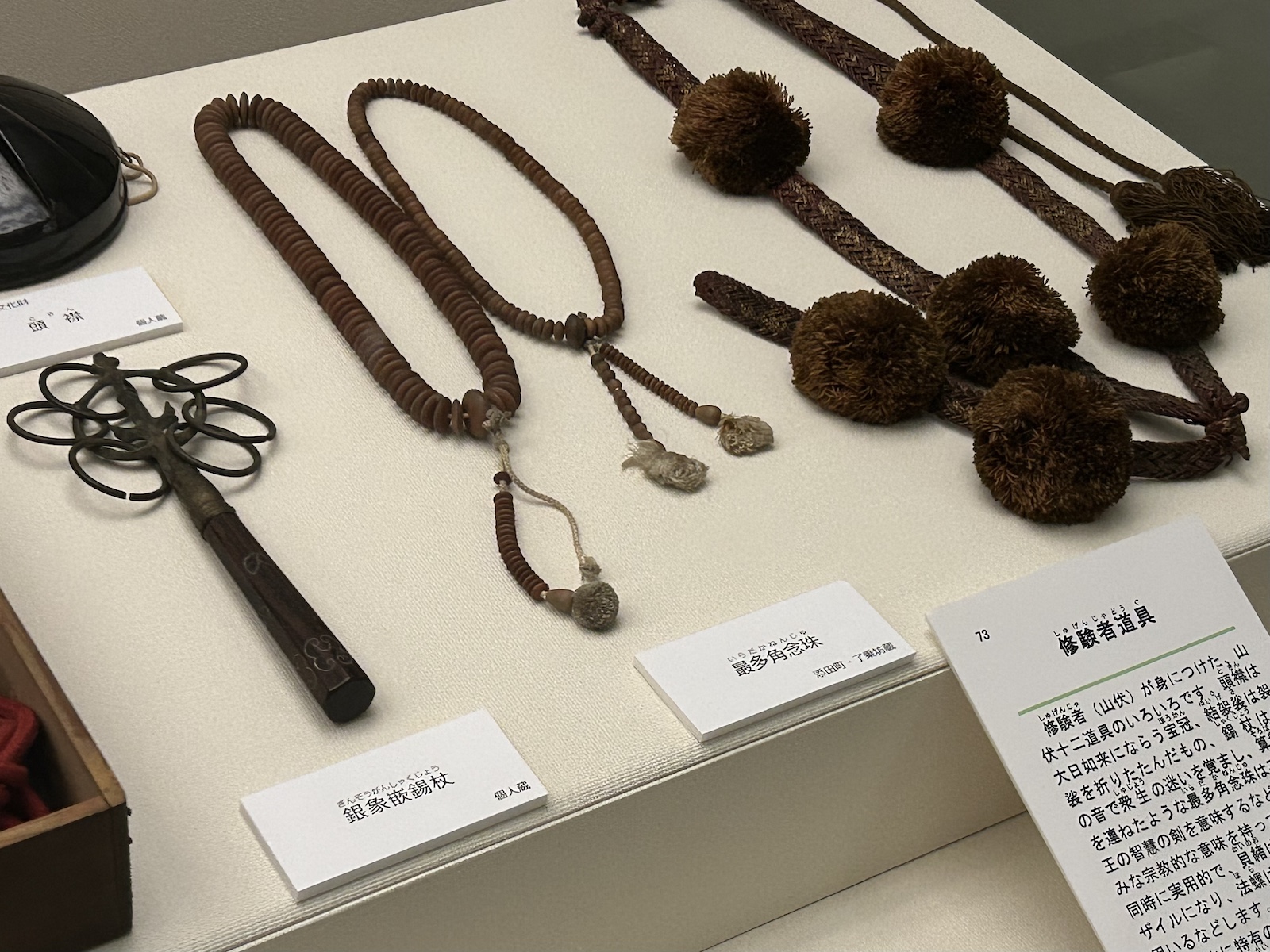

This history is recounted in exhibits at the Yamabushi Cultural Museum housed in the abandoned elementary school building near the bottom of the main shrine approach. Many of the relics displayed were kept hidden away for nearly a century by shugendo-practicing monks turned Shinto priests, and passed down from father to son. The building also contains a small shop selling various local products as well as refreshments.

Adjacent to the former school is Hana Station, the lower terminus of the Hikosan Slopecar, a sleek, modern cable car that carries visitors to Kami Station, near Hikosan Jingu, with far less time and effort than required to climb the 300+ stone stairs of the main approach. Departures are every 20 minutes between 8:40 a.m. and 5:10 p.m.; one-way fare is 350 yen.

For those who are enthusiastic about ascending ancient stone steps, the Hikosan Sando Kakeagari Taikai (Great Race Up the Hikosan Approach) is held annually on August 11 to commemorate the Japanese Mountain Day holiday. The deadline to enter the 2024 race is soon: June 30. Details are here (Japanese language only).

Visitors wanting to explore shugendo and the mountainside’s religious significance may also prefer to ascend the stone steps, slowly examining the ancient stonework and temple remains on the way to Hikosan Jingu. There are still a few small temples and shrines along the way, as well as a sweets shop and a small cafe.

Down the lane behind Hikosan Jingu is the Hikosan Shugendo-kan, a small museum of exhibits on shugendo worship on the mountain. It is open 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Friday, Saturday and Sunday only. Admission is 200 yen.

Hikosan Jingu’s central courtyard is a serene spot to stop for a rest. The helpful shrine staff there can provide further information on hikes and suitable hiking trails. On my last visit it had been quite rainy and I was advised that one of the main trails upward from the last of the stone staircases was too dangerous to attempt. Good to know!

When hiking conditions are good (most of the time, actually), there are a number of trails around the mountainside, which is especially well known for its autumn foliage but is beautiful any time of year. One of the longest and most challenging trails is a 15-kilometer circuit that visits all three of the mountain’s peaks in five to six hours. In addition to the natural beauty of the mountainside and its forests, the trail passes by Tamaya-jinja, a wooden shrine built into a steep cliff face. Each peak is also home to a small shrine structure.

This historical mountainside has so much to explore that, while it can be a day trip from Fukuoka, a bohaku overnight stay may be best to truly soak up the shugendo atmosphere and everything the mountain has to offer.

Getting There

The easiest way to reach Hikosan is by private car. It is about 1.5 hours from Fukuoka city. Using public transportation is more complicated, requiring three trains from Hakata Station to Hikosan Station (about two hours) and then a bus to Kane-no-torii, the copper-clad shrine gate at the very bottom of the ancient stone steps.

Vicki L Beyer, a regular Japan Today contributor, is a freelance travel writer who also blogs about experiencing Japan. Follow her blog at jigsaw-japan.com.

© Japan Today

No Comment

Login to comment